Holofernes, 1598-99)

In In May 2018 two famous contemporary (male) artists were scheduled to exhibit in the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. Both exhibitions were cancelled after allegations of sexual misconduct by the artists were made public.

In May 1606 Michelangelo Merisi, better known as Caravaggio, allegedly killed another man under debated circumstances, he was sentenced for murder and had to flee Rome. His artworks and legacy today are celebrated around the world.

In between those two cases there are generations of artists who held or acted on sexist, racist, conspiracy theorist, or antisemitic views. Many of these are widely exhibited, sometimes despite their personal views or actions and at other times enabled by a general oblivion of their personal lives.

What do 21st century #metoo cases have in common with 17th century murder and omnipresent hate speech or violence? How should exhibition spaces and we as consumers of art treat artworks by artists who have acted or are believed to have acted criminally, in physically or sexually violent ways, or with controversial political motives? Should a work of art by such artists be exhibited and viewed?

Different positions exist on what are acceptable behaviours and worldviews and what are not, and though I have personal opinions, I will not argue in favour of any side here. Instead I will suggest a framework that anyone can use once they have deemed an artist or their actions ‘morally unacceptable’ to help them decide whether or not to give that artist a platform by exhibiting them or visiting an exhibition of their works.

Firstly, despite some claims that it is a freedom of speech infringement to deny artists an exhibition space based on their personal actions or views, it is definitely an institution’s or gallery’s right to decide not to showcase certain artists and for consumers to decide to boycott an exhibition. The other argument often made by opponents of the so-called ‘cancel-culture’, is that if we were to stop exhibiting artists with dubious morals the walls of galleries and museums worldwide would be empty. This argument however is based on the false assumption that all “moral mishaps” would have to be treated the same. Just because shoplifting and sexual assault can both be labelled as immoral does not mean they are the same thing or that their perpetrators should receive the same treatment. Demanding not to show certain artist’s works due to their personal actions is not equivalent to requesting there should be no distinction between which actions qualify for this treatment and which do not.

But where to draw the line?

Proponents of this “empty walls” argument suggest that it is impossible to draw neat a line that separates ‘acceptable immorality’ from ‘unacceptable immorality’, and they are not wrong. However, while it is a difficult process that will undoubtedly leave some cases in a grey zone, it is nonetheless essential to have a debate about them.

Firstly, there is the respective national law under which jurisdiction an artist may fall. There is a reason that in democracies we give over the power of judging and punishing illegal deeds to an institution. This goes for private as well as public figures like artists and in those cases where an artist commits a crime they will be judged, sentenced, and punished for it by the state. Generally, if they have accepted their punishment and followed through with the sentence, they should afterwards be treated as rehabilitated. Therefore if an artist injures someone in a bar fight and consequently has spent 10 month in prison and paid x amount in reparations to their victim, they should not have any exhibitions cancelled because of this crime since their punishment has been dealt with by the justice system.

However, most justice systems are not infallible and there are cases where actions that ‘feel’ like they should be punished are not. This happens all the time for different reasons, be it technicalities, mistakes by law enforcement, lack of direct evidence, or simply because they are not actually breaking any laws.

Especially difficult in this context are cases of sexual violence, political radicalism and hate speech. All fall often outside the limits of the legal system and are the stage for the most common and fought over debates of whether or not to exhibit an artist. Sexual violence is in most cases illegal, but often difficult to bring to and win in court. Political radicalism and hate speech are often protected by free speech rights, but are nonetheless hurtful and have potential illegal consequences, e.g. in cases where it encourages others to violence against minorities.

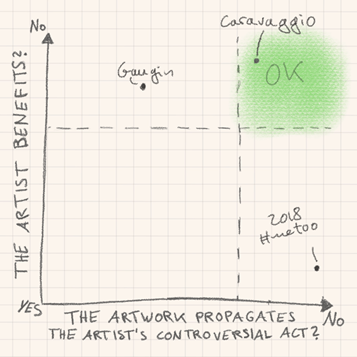

If a gallery or a consumer of art finds an artist’s engagement in such actions problematic and wonders whether it is still okay to exhibit, buy or view the art, I suggest to ask two questions. Firstly, will the artist profit from their works being exhibited, either socially, financially, or both? And secondly, does the artwork show or propagate the problematic ideas or actions that the artist is being criticised for?

Who profits and what does the artwork communicate?

In cases where the controversial artist will profit from the platform given to it by an exhibition or from our gallery visit it is a valid decision to withdraw this platform from them, as we might wish to not indirectly give money to someone who might use it for causes we do not support, e.g. to pay for a plea deal in a sexual misconduct case or to donate it to right-wing lobby groups. This will mostly affect contemporary artists such as in the 2018 #metoo cases mentioned above. Artists which have been dead for decades or even centuries will unlikely profit from or misuse the financial or social gains that an exhibition of their work will bring. In those case it might only be worth checking what individual or organisation is in charge of an artist’s estate, but these are often states, charities, or educational institutions that do not benefit individuals or controversial causes.

Apart from the question of who profits from the exhibition it is important to consider whether the artworks in question propagate or in some explicit form represent the questionable actions or ideas of the artist. There is a debate at the moment about the late 19th century French painter Gauguin’s depictions of girls and women from the French overseas territory French Polynesia, which have been argued to reproduce sexist and orientalist views of European colonialism and racism. So while Gauguin does not profit from his prominent position in the canon of Western history of art and the connected prominent exhibitions, we may ask whether the views underlying the presentation of his subject matters represent ideas that do not fit contemporary efforts to decolonialise museums. If we decide yes, they do represent ideas we do not want to give space to in the public discourse, then we might again decide not to exhibit or visit exhibitions of his artworks.

Taken together these guidelines would find that it is okay to not exhibit living artists against whom there are allegations of sexual misconduct as they would benefit from an exhibition, like the National Gallery of Washington decided in 2018, even if their artworks have nothing to do with violence against women. It was also show that it is okay to showcase Caravaggio paintings as he will not benefit from it (though he did use his fame as an artist to avoid persecution during his lifetime) and his works, although bloody at times, show biblical iconography common of church commissions at his time and are (currently) not seen to reproduce harmful worldviews.

Against the claims of the “empty walls” argument a process, which as a first step leaves the judgement and sentencing of artists to the state, where they are treated as any citizen, and as a second step seeks to avoid that controversial artists profit from or are able to propagate their views through exhibitions, allows for selective decisions against showcasing or visiting certain artist’s exhibitions without leaving the walls of galleries empty worldwide.