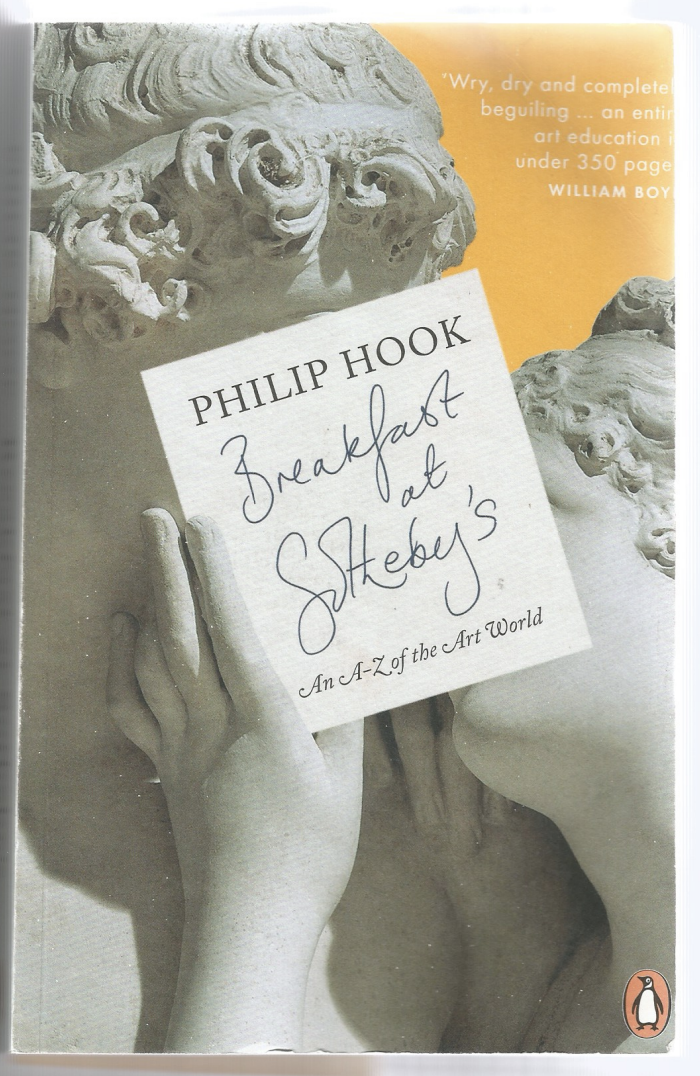

Cover of the book

The author Philip Hook in 2017

Credit: Sotheby’s

When you stand in front of a work of art in a museum or exhibition, the first two questions you normally ask yourself are 1) Do I like it? and 2) Who’s it by? When you stand in front of a work of art in an auction room or dealer’s gallery, you ask these two questions followed by others: How much is it worth? How much will it be worth in five or ten years’ time? And what will people think of me if they see it hanging on my wall?

The essential art toolkit to understand fluctuations in taste and economics of a dynamic field such as the art market. This is the relevance of “Breakfast at Sotheby’s – An A-Z of the Art World” published by Penguin Books in 2014 and written by Philip Hook, director and Impressionist and Modern art senior paintings specialist at Sotheby’s. This book is a 350-pages manual for anyone who is interested in discovering the basics of the art market and the process which confers art a financial value. But don’t worry, you don’t need to be studying history of art in order to enjoy this beguiling text.

The structure of the book is composed of five parts, each representing a different key factor in determining the price of an artwork. Starting from an analysis of the artists and their background, moving to subject and styles and how these end up influencing taste, continuing with understanding what pushes a buyer to acquire an artwork and concluding with the functioning of auction houses and the roles of the dealers nowadays. The organization of the chapters and the division of the subtopics of this book resembles a vocabulary with the addition of a personal memoir of Philip Hook’s experience in the art world.

The book starts by laying the bases of the art market and moving on from factor to factor, developing an engaging reading. Philip Hook’s writing style reflects his unique wry humour which emerges in every chapter, transforming the book in a surprising discovery of art from an internal perspective of the art trade. Instead of exclusively highlighting the positive aspects of the art market and the auction houses, as it may seem at the beginning, Hook points out the internal dynamics and the controversies that characterise this world. The narrator’s voice guides us through a recollection of his memories when working at Sotheby’s and Christie’s. One of the anecdotes that Hook tells us about is his first assignment at Christie’s when he was asked to catalogue a ‘cardinal’ picture without having heard of this type of art before. Later in the chapter, we find out that these ‘cardinal’ pictures were popular in the 19th Century and at that time reached the value of a small Picasso painting. They included mockery depictions of noble figureheads of the Roman Catholic Church and interestingly, this painting genre was fashionable in a time in which anticlericalism prevailed. The conclusion that reaches Hook thinking about this topic in relation to the current art world is that institutional critique is a selling factor, pointing out the popularity of Francis Bacon’s depictions of popes who scream and Maurizio Cattelan’s sculpture of Pope John Paul II while being knocked over by an errant meteorite.

George Croegaert, Private Indulgence, c. 1890, Oil on panel

Francis Bacon, Untitled (Pope), c. 1954, Oil on canvas

Maurizio Cattelan, La Nona Ora, 1999

What I particularly liked about this book is the fact that Hook did not step back when there was a need to criticise his professional field. Instead, he mocks his trade’s absurdities and is not afraid of exploring subjects such as missing paintings and art theft, and even pointing out the most saleable periods of 50 artists, ranging from Giacomo Balla to Édouard Vuillard. Amedeo Modigliani’s most expensive artworks comprise of female nudes, Piet Mondrian’s have to include the red colour, Paul Klee’s most desirable paintings are the ones completed in a trip to Tunisia in 1914, Constantin Brâncuşi’s sculptural abstraction is much more prized than his representational early works. These are just some of the interesting notes that Hook introduces in the book.

Constantin Brâncuşi’, Maiastra, c. 1912, Polished brass

Credit: Succession Brancusi

Paul Klee, Saint Germain near Tunis, 1914, Watercolour on paper

A few chapters could be debatable, for example, Middlebrow Artists in which Hook writes a list of artists who are not respected anymore because of their excessive popularity. The justification for this, explains Hook, is that too many people like them and therefore the art specialists dismiss them as too easy. And although the title confers a negative impression on the perception of their art, stating that we will probably never see a retrospective at Tate Modern or the New York Museum of Modern Art on these artists, Hook admits that their artworks are sold for high prices on the international art market. Some of the artists that were included in this list are Bernard Buffet – one of the key figures of post-war Misérabilisme, Jack Vettriano – a Scottish artist of Italian origins unrepresented in major museum collections, and Thomas Kinkade – labelled as excessively kitsch for the current art market taste although one of the most collected artists in the United States. This debatable chapter creates a slight confusion on the metrics used to determine whether an artist is excessively popular until becoming ordinary and taken for granted. Hook does not draw on the specifics that derive from this negative trademark – which, at the same time, does not negatively influence the artworks’ value. Although it fails at giving objective bases on which to draw his conclusions, it is a useful chapter to point out the absurdity of the art trade. On the other hand, it has to be said that the vocabulary structure of the book imposes a synthesis of the argument which sometimes results in a thesis not fully developed.

The relationship between art and money, as much as it repels some art lovers, is undeniable in today’s world. The most famous auction houses – Sotheby’s and Christie’s – were both founded in London respectively in 1744 and 1766 and have survived through war disasters and financial crisis. Selling art is not a very objective discipline and is fulfilled by “fantasy, aspiration and human rivalry” as Hook himself declares. This is what renders this field so unique, the way in which it combines a discipline of humanities and one strictly related to numbers and financial strategies. Taking into consideration the last twenty years, the art market has been internationally recognised as an emerging economy. Therefore, understanding the functioning of the art trade is crucial because even by analysing the contemporary market in particular, when an artist is included in a Sotheby’s or Christie’s sale, this increases the importance of the artist himself, consolidating his/her brand and giving him/her new opportunities. Hence, it is important to highlight the fact that art is intrinsically tied to marketing and finance but at the same time, this does not deny the crucial position that art historians and specialists occupy in this field.

Oliver Barker leads Sotheby’s July 28 evening auction “Rembrandt to Richter” from the London saleroom

Credit: ARTnews

More about Philip Hook. He studied History of Art at Cambridge and has worked in the art market for thirty-five years now, starting at Christie’s, continuing as an international art dealer and lastly landing at Sotheby’s. He is the author of several novels and works of art history, the last of which is titled Rogues’ Gallery: A History of Art and its Dealers, published in February 2017. Hook has appeared regularly on television, from 1978-2003 on the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow as the painting specialist.

Sounds like quite an entertaining read! …although I think art dealers and artists inhabit very different realities!! 😀

I think art dealers and artists inhabit the same reality but have very different visions and ideas to act on it.