There is no looking glass here and I don’t know what I am like now. I remember watching myself brush my hair and how my eyes looked back at me. The girl I saw was myself yet not quite myself. Long ago when I was a child and very lonely I tried to kiss her. But the glass was between us—hard, cold and misted over with my breath. Now they have taken everything away. What am I doing in this place and who am I?

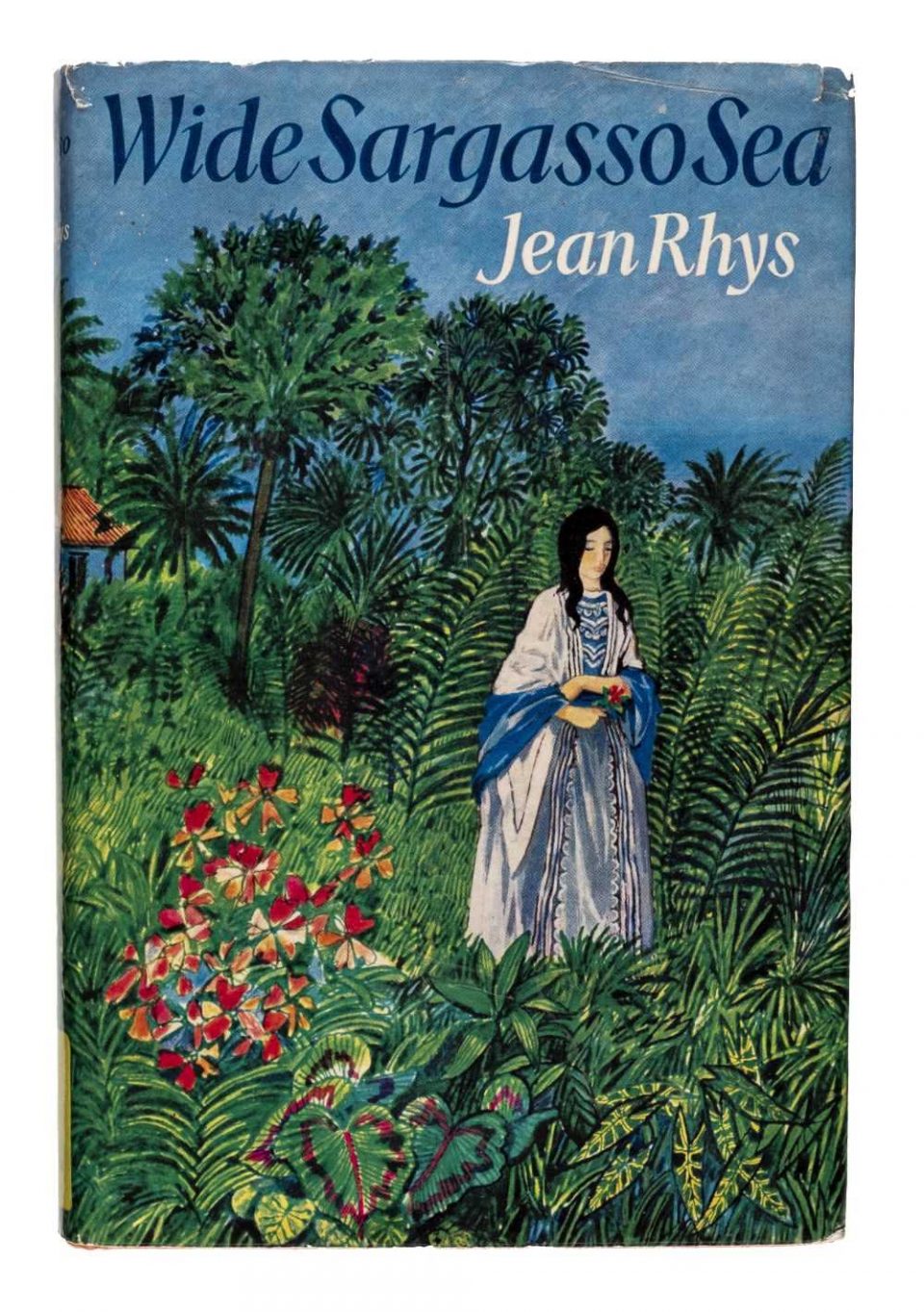

Wide Sargasso Sea, Jean Rhys

Wide Sargasso Sea is a highly praised literary work and the most famous of the postmodern author Jean Rhys. The protagonist is called Antoinette, a beautiful Creole who lives her childhood on a Caribbean island, in the period immediately after the abolition of Jamaican slavery. She soon finds herself faced with several difficult situations: she grew up far away from her mother who went mad immediately after the loss of her youngest son, the protagonist’s brother. Additionally, when Antoinette was very young, she also married a rich English man, Mr Rochester, who immediately shows a certain attraction for her world but not for her; he seems more attracted by what surrounds her – landscape, history, voices, legends – preventing him from falling in love with his bride. At the end of the story, he tears the young girl away from her native land, locks her up under the British grey sky until she goes “mad” and reacts in an excessive way.

[Credit: https://generallygothic.com/2020/03/03/wide-sargasso-sea/]

In Wide Sargasso Sea, Rhys addresses the issue of femininity and the role of women alongside themes such as colonization, racism, deportation and touches also on the concepts of identity and belonging. Antoinette is in fact “a stranger”, she is an outsider from many points of view: as a Creole, she is not considered to entirely belong to neither the white nor to the black community, even though she is a native of the Caribbean islands. As the daughter of a woman who is no longer mentally stable, she is subject to the prejudice of possible madness. As a daughter – and a woman – her own destiny is imposed on her, determined first by her father and then by her husband. This last aspect, although central to the discussion of gender that rightly affects the novel, is relevant also when analysing the male counterpart. In the same way as Antoinette, Rochester is a second-born; according to the English law of the time, he does not have the right to inherit any family property nor oppose his father’s will, which forces him to leave the British homeland for the Sargasso Sea islands. However, he subjected Antoinette to other strangenesses: first of all, to the one towards her own identity, giving her the name “Bertha”, and at the end, to the one towards the place where she lived, snatching her from Jamaica and taking her with him to England. The woodworm of jealousy soon creeps into the couple making Antoinette’s outbursts excessive to the limit of madness, and he – driven by contempt – starts calling her Bertha, like her crazy mother. Giving a person a new name means giving her a new identity; doing it against her will is the first step towards psychological violence. “Bertha is not my name. You are trying to make me into someone else, calling me by another name. I know, that’s obeah too” (Wide Sargasso Sea, Jean Rhys).

[Credit: https://www.dominicwinter.co.uk/Auction/Lot/rhys-jean-wide-sargasso-sea-1st-edition-1966/?lot=353059&so=0&st=&sto=0&au=736&ef=&et=&ic=False&sd=1&pp=24&pn=14&g=1]

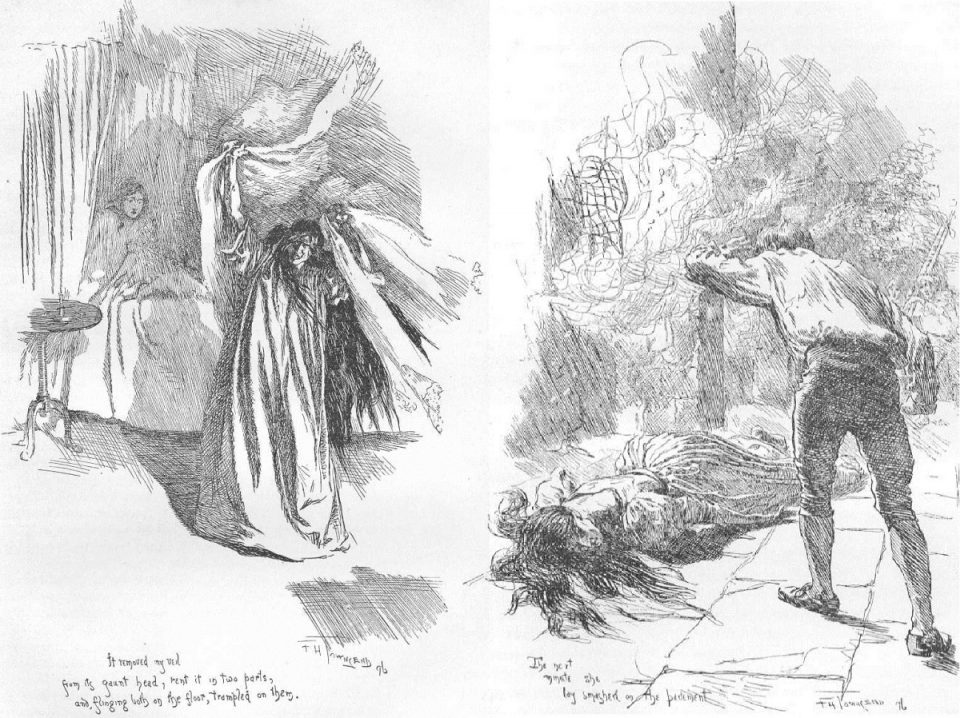

Now, although you have never heard of Wide Sargasso Sea, the names Bertha and Rochester are not new. This is because Rhys’s novel is considered the first spin-off in literature; in fact, it is a prequel to Jane Eyre, the most famous novel by the most fortunate of the Brontë sisters, Charlotte. For those who don’t know it, Jane Eyre talks about this young girl who was born without her parents, who lived with obnoxious relatives and who fell in love with the rude man she worked for in her adolescence – Mr Rochester – nothing you haven’t already read. The story becomes interesting when the marriage between Jane and Mr Rochester does not take place because of the discovery that he is actually already married to a certain “mad” woman named Bertha Mason. Fast-forward to the end of the book, **spoiler alert** Jane manages to marry the man after he goes blind in a fire caused by the infamous Bertha, where she comes out dead. Happy ending. The book was praised by the critics of the time and still chosen in all English Literature courses as one of the fundamental texts of the nineteenth century on a par with Dickens and Austen. The real problem lies in the description of the main antagonist Bertha; Brontë briefly describes the wife with the usual negative stereotypes with which nineteenth-century literature identified the inhabitants of the colonies. The impact that Brontë’s novel had and still has on the black community is very strong. Quoting Tyrese L. Coleman’s article Reading Jane Eyre While Black – which clearly shows the difficulty in accepting such a stereotypical and negative description – “I no longer have to participate in the mental gymnastics that were required to turn white protagonists black. I don’t have to read a book like Jane Eyre that makes me feel shame for relating more to the demonic, non-white villain than the actual heroine.”

[Credit: https://thelongvictorian.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/list_janeeyre_bertha_both.jpg?w=1200]

Wide Sargasso Sea could appear as little more than a dramatic love story, well written of course, but without much more. Instead, the narrative structure of the whole story is extraordinary: Jean Rhys, with Antoinette’s story, has not only reconstructed the stages of an inexorable dissolution, of a failed marriage; not only she explored the difficult connivance between whites, blacks and Creoles; not only she reflected on the immovable dominance that the male wants over the female; she has also reconstructed, in a fascinating intertextual leap, the story of the character of a madwoman, wife of the male protagonist, who appears in Jane Eyre. As if struck by this literary shadow, Jean Rhys gives her a face, a story, a dignity that perhaps allows those who have read Brontë’s novel to redefine certain coordinates. She does not reinvent nor modify Brontë’s character but gives her back that human dimension that in the pages of Jane Eyre is denied. Her madness is the desperate reaction to her condemned isolation, to the drama of not knowing whether she is black or white, to her unfulfilled desire to belong. “’Is there another side?’ I said. ‘There is always the other side, always” (Wide Sargasso Sea, Jean Rhys).