“I want to distort the subject way beyond its usual appearance, but, in the distortion, bring it back to a delineation of its aspect […] It is thus conveyed the sensation and the sense of life in the only way possible” (David Sylvester, Interviews with Francis Bacon, p. 41)

This is how Francis Bacon, Irish-born British figurative painter of the 20th century, describes his work, rejecting any classification and claiming that he strove to render “the brutality of fact.” A life pervaded by the obsession for fragments, Bacon decides to become painter in 1927, after seeing an exhibition of the Surrealist Picasso in Paris. From then onward, his creative imagery is invaded by frames and images from various sources, from Renaissance painters to contemporary photographs and films, which chaotically accumulate in a stratification of memories, inspirations and references.

Francis Bacon Studio at the Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin

Image credit: Bianca Callegaro

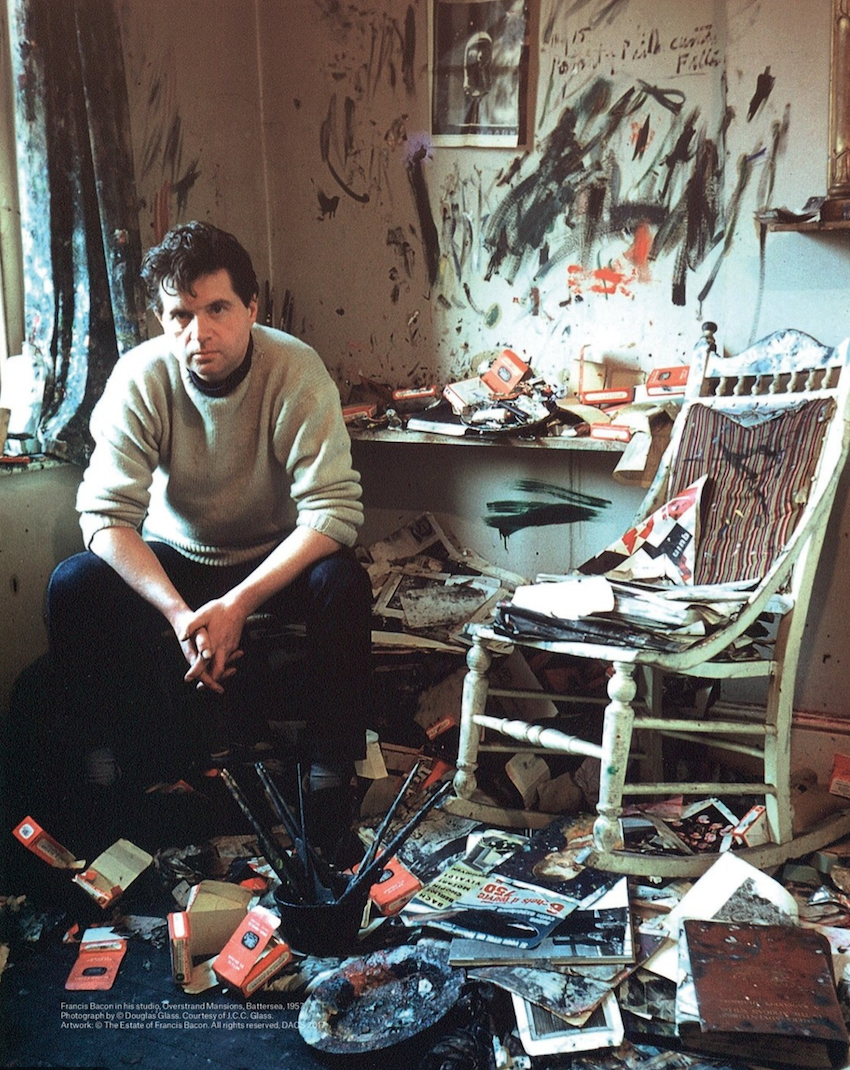

Francis Bacon at the Battersea Studio (1957)

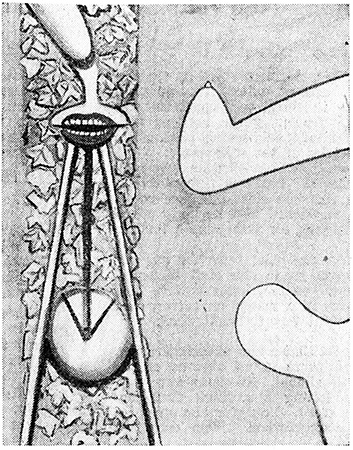

Eisenstein’s 1925 silent film Battleship Potemkin has a particularly strong impact on the imagination of the young artist. Especially striking to him were the frames of screaming mouths that recur in the film, which become a constant source of reference in his future works, an early example of that being Abstraction from the Human Form (1936) together with the well-known later series of Heads (1948-49), which features variations upon the theme of deformed figures that emerge from the background’s darkness.

Frame from Sergei Eisenstein’s Potemkin Battleship (1925)

Francis Bacon, Abstraction from the Human Form (1936)

Francis Bacon, Head VI (1949) Hayward Gallery, London

Rejected by and rejecting the Surrealist movement during the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition, Bacon starts his artistic career anew, destroying most of his previous canvases and focusing on iconography and the typically religious formats of the diptych and triptych, with the triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944) being his first major breakthrough and marking the origins of his celebrated signature style. In this painting, Bacon transports Christian iconography into another historical dimension, turning the three religious figures of John, Magdalene and the Virgin Mary into mythical monsters, almost like the Erinyes, the vengeful characters from the tragedies of Aeschylus.

Tate Britain, London

Like the succession of events that characterises human history, a series of fortuities that accumulate one upon the other, in the same way the references to the history of the visual arts are vortically collected in the works of Francis Bacon. From Rembrandt to Velazquez, from Raphael to Leonardo, the artist evokes the figurative tradition of the Great Masters to radically transform it through his reinterpretation, cutting off every commonality with tradition. His use of renowned image fragments becomes revolutionary as he overturns their symbolic suggestions, transforming the figures that inhabit his canvases into messengers of the gritty and gloomy reality of human life. When responding to criticism on the extremely violent nature of his art, Bacon stated that “there might be an element of realism in my work that might give this impression, but life is so violent much more violent than anything I could ever create” (Michel Archimbaud, Francis Bacon In Conversation with Michel Archimbaud, p. 151).

The representation of reality as intrinsically violent bonds Francis Bacon with another cutting-edge artist from the 16th century, namely Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Without being directly influenced by Caravaggio’s oeuvre – which he admired in 1954 during a visit to Rome – Bacon seems to share a similar artistic outlook with the Italian artist, pioneering emblem of modernity in art. Such a parallel was explored by Galleria Borghese (Rome) in 2009, with the exhibition Caravaggio-Bacon. The juxtaposition of artworks by the two artistes maudits aimed to provide visual suggestions and spontaneous correspondences, rather that a historical-critical reconstruction of the (unlikely) dependence of Bacon from Caravaggio. The exhibition does not indeed operate through direct comparisons, in accordance with Bacon’s modus operandi, which refused any direct connection with artists of the past and always worked through the filter of the photographic medium, allowing these references to intuitively pervade his creativity. Both artists, despite formal and epochal differences, have fathomed with originality the mystery of human existence and art, representing spiritual truth through the traumatic immediacy of the flesh.

In direct lineage with the great tradition of the Italian Masters of the Renaissance, Caravaggio adopted a ground-breaking style, bringing upon a schism in the history of art with his style. No longer portraying an idealised reflection of the world, Caravaggio transposes the historical and the religious into the ordinariness of the life of contemporary men and women, using them as models to tell Biblical stories in a modern disguise. He does so in a shockingly realist style which, combined with a dramatic use of light and contrast (chiaroscuro), allows for the expression and analysis of the tragical mystery of the human condition. His technique “a risparmio“, which is to heavily influence the Baroque style, consists in preparing his paintings with a dark layer, the base from which the figures emerge by illuminating part of the canvas. The artificial, theatrical light that brings back elements from the darkness seems to have much in common with Bacon’s paintings, which often feature cage-like structures that trap the figures surfacing from dark blue backgrounds. Both artists eliminate the superfluous from the canvas, allowing the protagonists of their stories to arise in full force, dramatically emphasised in their raw representation. Therefore, finding parallels between the mute screaming mouths of Caravaggio and the deformed cries of Bacon’s human monsters is almost expected. Living in solitude and separated from any artistic trend, the two artists clean the slate of art history, substituting repeated formulas with a tabula rasa which primarily aims to represent reality in its purer essence, even when that means depicting violence and brutality.

Detail from: Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath (c. 1610), Galleria Borghese

Francis Bacon, Study of a Head (1952)