We are ending this week which approaches russophile art on different scales with Gelij Korzhev, an artist renowned for having evolved in style in parallel with the Cold War, going from his “severe style”, particularly appreciated by the USSR, to a personal delusion of a political dream.

I had the opportunity to discover Gelij Korzhev (1925-2012) for the first time in 2019, at an exhibition called “Gely Korzhev, Back to Venice” which was partly intended to reconstruct the Russian pavilion as well as its works as at the 31st Venice Biennale held in 1962. The choice stemmed from the fact that not only for years the Biennale had been suspended following WWII, but also that the Russian pavilion specifically had aroused very different reactions , reflecting the opposing geopolitics of the times.

During that Biennale, Soviet art was not considered to be backward as compared to Western contemporary art. If on the one hand the Americans stood out with Abstractionism, exemplified by Pollock’s action painting, the Soviet art at the pavilion seemed austere. The art critic representing the Italian Communist Party, Micacchi, read the Russian paintings full of dark and gray tones as typical of the traditional academy of the previous century, limiting them to “paintings more for the eye than for ideas”, which brought nothing more beyond the aesthetic (Bertelé, 2017).The criticism lied on the “gap” between Russian scientific progress vis-à-vis a purely academic and old-style art.

As for the Russians, on the contrary, this pavilion knew an unprecedented freshness. Just before the opening of the Biennale, the head of Soviet art exhibitions abroad had died, and instead, a young curator of Italian drawings at the Hermitage, Larissa Salmina, found herself taking on the task. She seized the opportunity to bring to the forefront of the international scene young artists, including Korzhev, whose aim was to extend Soviet Realism to a complete realism, which covered both the negative and positive aspects of daily life: offering spectators “the truth of life” (Burini and Barbieri, 2019).

In fact, Korzhev rejected the pictorial canon of the idealized naturalness that preceded him. Instead, he focused on the physical and moral impact of the war on people, yet his artworks make the subjects appear suspended in time. This successful style had been coined by the Russians as “severe style”, because it is characterized by a gloomy and simple color palette, and the subjects are people who, having suffered the consequences of war (soldiers, widows, the physically handicapped), do not need further ideological propaganda: they are aware of their national honour values, and are ready to live firmly and willingly in and for the URSS. Following a visit to London where he noticed several street artists asking for money, Korzhev painted The Artist (1961) exhibited at the Biennale. In this perspective, he criticised commercialization and trivialization of art in the west, which forces the artist to be subjugated to the demands and prices of the public.

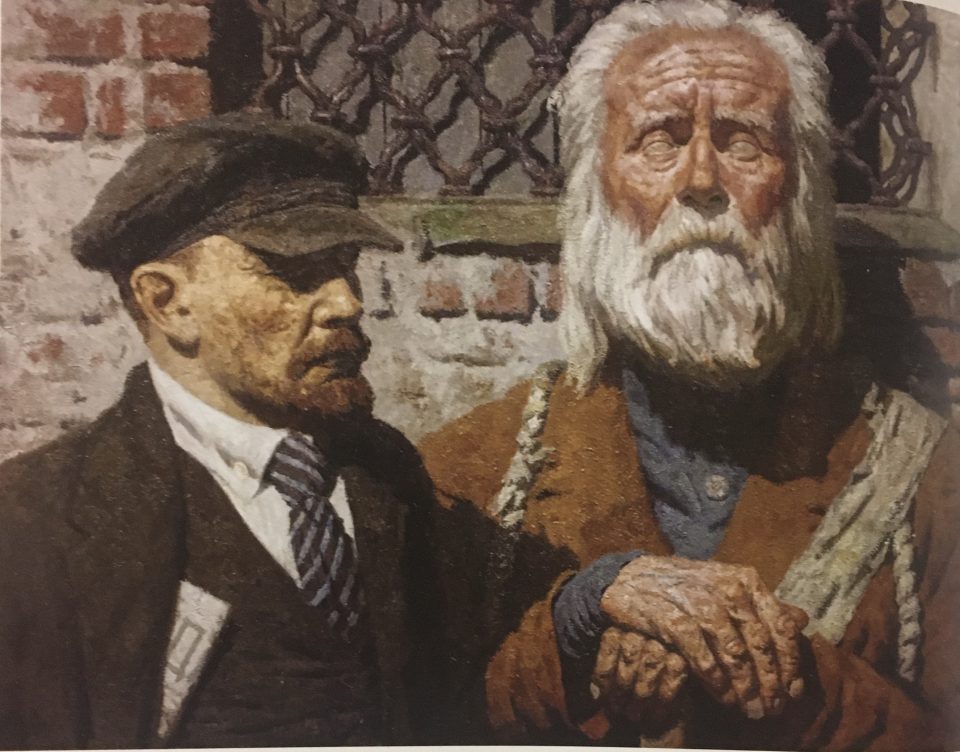

Over time, Korzhev testified a political change, translating it on his canvases. The artist distanced himself from the regime, and a tone of ambiguity began to emerge from his artworks, such as The Conversation (1980-85). Two people standing: a man representing Lenin and a typical farmer. They represent two opposed lifestyles; one the city, with a futuristic notion of time (always going forward), the other instead painted in a traditional way, embodying the countryside and its cyclical rhythm of living. The elder is blind, and one could say that since people are lost in a political sense, Lenin is allowed to deal with the future of the country on their behalf. Or you could even say that the people are blinded by following communism. Yet, aesthetically speaking, Lenin and the elder are painted with the same technique, making them equal to each other, as if the history of the USSR is common to all people of the USSR. The ambiguity of the canvas reflects the ambiguity of the artist in his art for the state, which later became more and more critical.

He became increasingly disappointed with the state of civilization, and consequently his national hero-like sitters change. They pass from a heroic aspect into disturbing monsters, similar to the creatures of Bosch and Goya. These hybrid beings called tjurliki (semi-human mutants) find themselves celebrating absurd encounters, often with a leader calling to an uninterested group of fools. The use of the beasts unexpectedly brings Korzhev closer to Western postmodernism, thanks to the deliberate distortion of the body, almost as a reference to Francis Bacon.

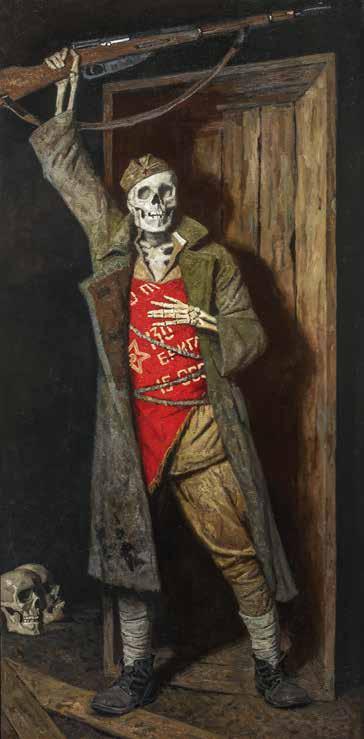

Towards the last years of his life, this disappointment acquires almost a self-deprecating tone. In The Victory of the Living and the Dead (2001), the standing soldier reminds those painted and exhibited at the 1962 Biennale (see The Raising Flag). Yet, instead of the face, there is a skull, in the spirit of danse macabre (the late-medieval representation of skeletons celebrating with humans). Korzhev, initially among the main representatives of that Soviet realist vanguard, makes the soviet heroes disappear, both physically and sensibly.

Wow, what an interesting selection of paintings! I think his change in style really illustrates the power of art….to question not just the wider reality, but one’s own perceptions of that reality. There is so much to learn about Russian art! Thanks 🙂

Thank you for your lovely comment! Russian art is a whole world to discover, that’s for sure!