Clyfford Still (1904-1989) was a key figure in Abstract Expressionism, more specifically within the New York School – eventhough he was the only artist who was not from the big apple. Because of his austere and reticent character, there is not nowadays as much research and interviews that have been done to him as, for example, to his contemporary and colleague Jackson Pollock. It is this anonymity which pushed me to discover him through one of his early artworks currently showcased at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, entitled Jamais (1944). I briefly introduce him from a biographical perspective, then I will follow with the artistic movements that influenced and elevated him in the art world – more specifically how he came into contact with Peggy Guggenheim, the most important female figure in post-war american art . While pointing out what made him a special character, I wll also illustrate his pictorial characteristics illustrated in Jamais (1944).

Clyfford Still was originally from North Dakota, North Central America, and as a teenager his family moved to the Washington state. He had been fascinated by fine art ever since, and his biggest dream was to visit MoMa to see for the first time artworks that he studied and copied on his own. However, once he accomplished his dream, Clyfford was very disappointed with the environment of the artistic institution, and from that moment on, he had vowed to himself to adopt a distant artistic approach to this world that he found pretentious. Indeed, this detachment was also reflected during his university studies. If he succeeded in entering the prestigious Art Student League of New York, he left 45 minutes after his first lecture, and decided to devote himself more to painting in his student’s room. Despite this strained relationship with art institutions, and love for making art, he later ended up becoming a professor of art at several universities, including Washington University and Spokane University.

At first, he was greatly influenced by Surrealism imported from mainland Europe as an avantgarde movement However, as he developed his own style and received greater appreciation from the public, he slowly moved further and further away from this movement. He believed that Surrealism was too specific and literal for the artist and too restrictive for the viewer, as it imposed titles and reading tools for the interpretation of the work, killing any freedom of interpretation.

“I reject the solution of antique protest, namely Surrealism initiated by Breton and Duchamp, and to adapt to new idioms from exotic cultures, referring to Picasso and Modigliani.”

To better understand his refusal, it is necessary to recall that Still began his artistic career in the 1940s, therefore ten years after the height of Surrealism in continental Europe. It was thanks to the meeting with Mark Rothko in 1943 that he was introduced at the New York School, what would become the leading group of Abstract Expressionism. What unified the members of America’s first international art movement, which included Rothko, Kooning, Pollock, Clyfford and others, was the way they all individually dealt with paint as a way to approach existential themes: life, death, despair, exclusion, hope, and so forth.

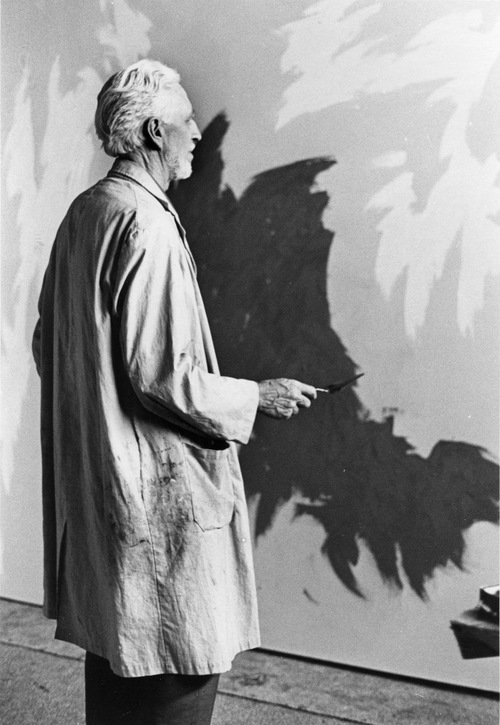

The absolute freedom of expression with paint and other materias was based on the theory of the man by Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980), a French philosopher whose publication of Existentialism (1945) was warmly received in New York. Here, Sartre put forward individual action, instinct, personal responsibility and the freedom of man – of the artist – and strongly inspired young left-wing apprenticeship artists who were to become known as abstract expressionists. It is in this context where we can imagine and understand Still who started using a palette, knife and trowels to spread his handmade paint over the surface, and taking distance, but not rejecting entirely, the surrealist influence.

Parallel to the emergence of this group came Peggy Guggenheim (1898-1979), that in 1946 decided to exhibit the group in her first gallery in New York, called Art of the Century (1942-1947). Rothko contributed to the catalogue, and specifically described Clyfford’s approach to art and themes as very close to those expressed within Abstract Expressionism, and therefore deserved to be exhibited in New York, a city that had replaced occupied Paris as the new artistic center of the western world. He was the only non-New York resident abstract expressionist artist that Peggy exhibited. Peggy described Still’s work through the pen of the critic Herbert Read

“there is a melancholy, almost a tragic sense incorporated into the paintings which makes them seem particularly near to one now”

Still’s artistic autonomy and his desired distance from the art world have not been widely accepted by everyone. Not only had he refused to be classified as a Surrealist, but he had imposed many restrictions on the way his works were to be exhibited. First, he refused any art critic to enter and write about any of his exhibits, as he believed that any traditional view of the academic world was an uninteresting judgment. In addition, he occasionally refused to let the so-called “passive visitors” enter his exhibitions: those that to him had no idea of his work or of the artistic movement. In the end, every time he received offers to make an exhibition, he accepted them under very restrictive conditions: only his works could they be exhibited, without collaborations with further artists.

One of the most striking anecdote was when he refused an offer from the Venice Biennale that was willing to exhibit him alone. He replied that exhibiting at the Biennale would go against his ideological position towards the institution. Personally, I believe that although some saw him as highly self-centered and intolerant, his approach is definitely more relevant because he challenged what was perceived as taken for granted in the art world. Unfortunately, this behavior resulted also in a lack of research and documents on the artist.

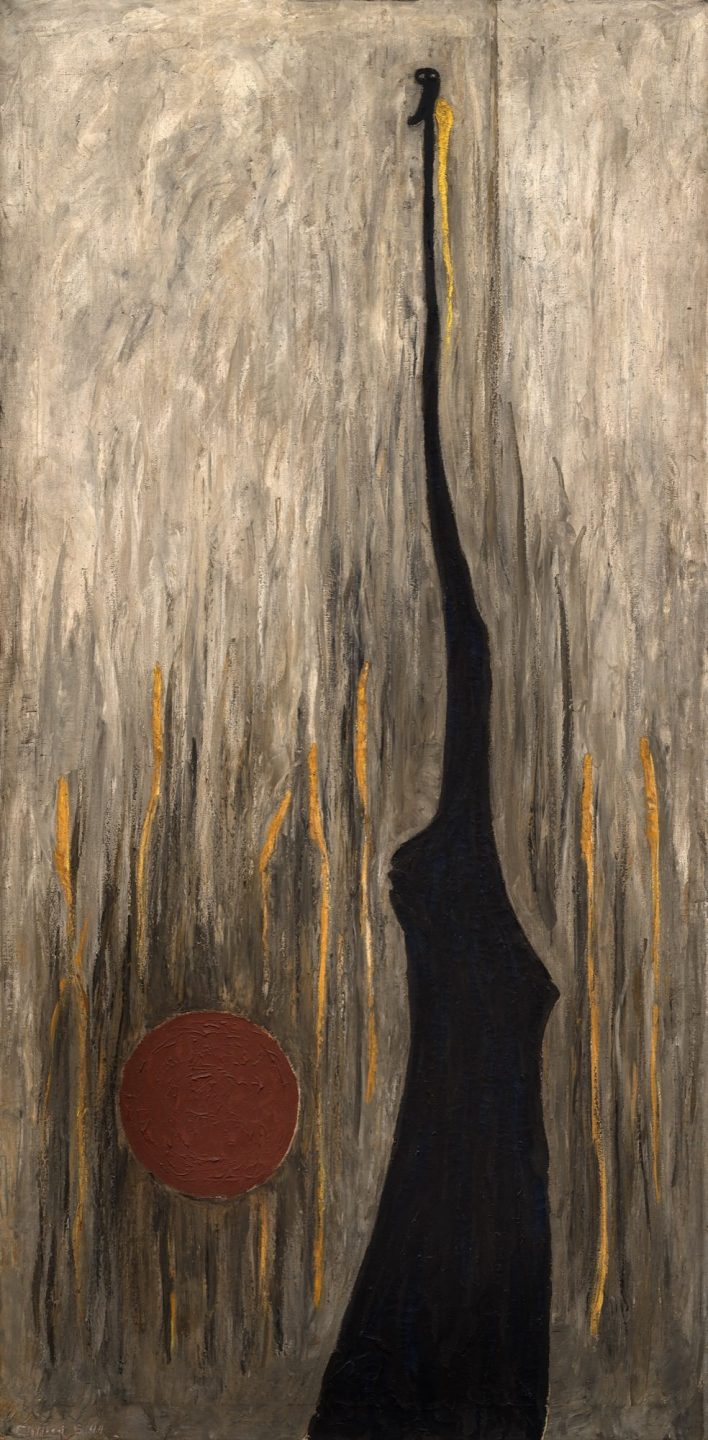

Jamais exemplifies some interesting paradoxes of the artist. Although he later rejected surrealism, he initially took inspiration from the unconscious, and transposed this philosophy into anthropomorphic figures that make a reference to myths. This painting echoes the myth of Persephone. The long-standing creature could be an allusion to Demeter, her mother, desperately looking for her daughter kidnapped by Adhes. The figure of Demeter recalls those of Mirò, in its expressionistic distortion and simplicity in the features. Yet the elongated figure has something mystical about it, and takes the form of a Native American totem. Here we grasp the uniqueness of this art movement to which Still leaned: many artists initially learnt Eurocentric art knowledge, and gradually began to insert references to their territorial culture.

Although the lips of Demeter can be distinguished, it is an abstract figure as a whole: it seems a black cut on the canvas, against the grey background, as if there were two layers of different colors one overlapping the other. Demeter appears as a crack between the patches of color, and the latter are so vast as to create space. Still managed to find a way to convey emotions through abstract means. Thanks to the cut on the canvas, one can relate to the pressure of the scene. Demeter’s neck emerges from the yellow flames, making a scream in vain against the passing of time, as the sun below is ending the day leaving no hope.

This artwork can be seen at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, currently running the crowdfunding campaign “Together for the PGC” so to keep its collection and didactic activities opened despite the COVID-19 crisis: https://www.guggenheim-venice.it/en/support-us/donate/

If you would like to learn more about the artist, have a look at the Clyfford Still Museum, in Denver: https://clyffordstillmuseum.org/