To conclude the week dedicated to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, I would like to tell you about the legacy of the current collection. Most of the works on display in Venice come from Peggy’s previous artistic initiatives as an early collectionneur. One of these was the New York gallery called Art of the Century that even though it lasted five years, it proved to be one of the most innovative galleries of the time in America.

Firstly, I will talk about what preceded the construction of this gallery in the 1940s from a historical and artistic point of view. Then I briefly present the exhibition catalog as it reveals Peggy’s innovative position in the field of art. I will illustrate the two rooms of the gallery by combining Peggy’s two artistic preferences: Surrealism and Abstract Art. Finally I will show you some of the works on display, which you can see in Venice.

Peggy moved to Paris when she was twenty-two and married Laurence Vail, a Dadaist she had previously met in New York. It is through Vail that Peggy attends bohemian salons and befriends early European avant-garde artists, such as founding members of Surrealism André Breton, Max Ernst, Jean Arp and René Magritte. Some other artists she knew there would later emigrate to America with her help, including Man Ray, for whom she posed, Constantin Brâncuși and Marcel Duchamp. She opened her first “Guggenheim Jeune” gallery in London in 1939, but with the advance of the German army, and given her Jewish origins, she flew back to New York. Her collection was temporarily entrusted to the Museum of Grenoble which, in 1941, securely sent it to her in America.

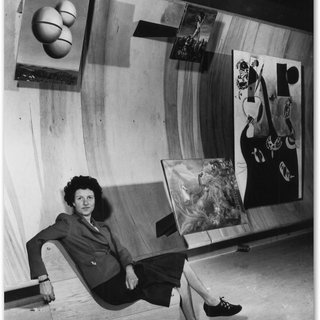

During the war, many artists and writers who emigrated from Europe found refuge in New York, which suddenly became a much avant-garde city than occupied Paris. Peggy had been disappointed with the London and French bureaucracy. She felt that in New York, thanks to the geographical distance from the conflict, she could easily open a new gallery. The Art of This Century was at 30 West 57th Street, and being located on the seventh floor, with the façade not facing the street, Peggy thought about creating something unique to attract people. She assigned this project to Frederick Kiesler, the Viennese Futurist architect, to set up the gallery in an innovative way. Once completed, the gallery was inaugurated in 1942.

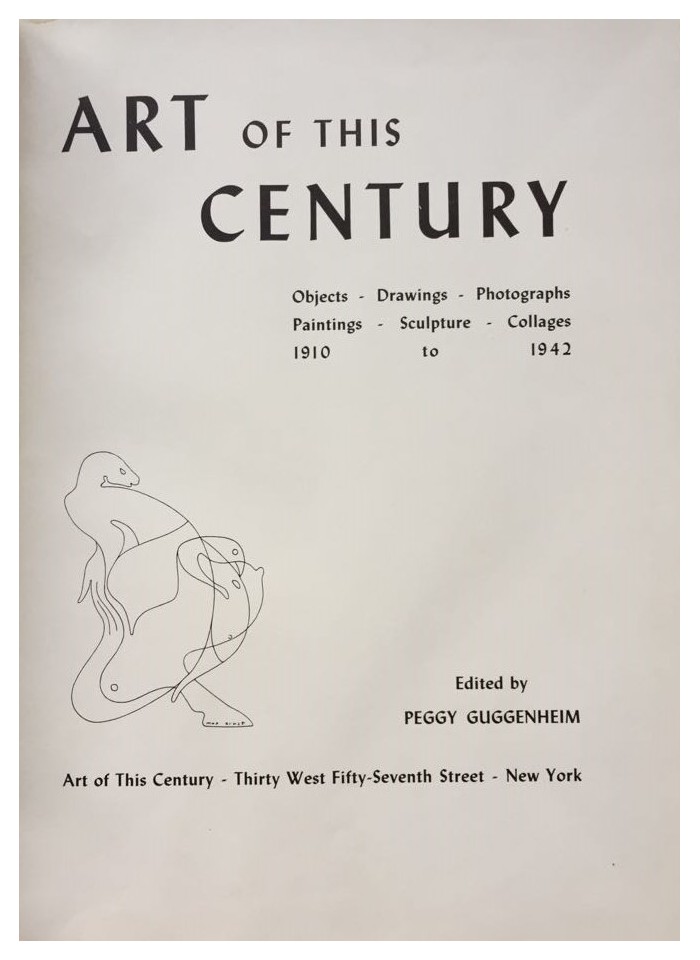

With the advice of the Surrealist painter Max Ernst and the poet André Breton, she published a beautiful catalog for her gallery. The introduction of the catalogue states: “ this catalogue has, to my great surprise, become an anthology of non-realistic art covering the period of 1910 to 1942.” The artistic movements covered in this time frame are explained by three authors who wrote in the catalogue, namely André Breton, Jean Arp and Piet Mondrian.

In the first part, André Breton (1896-1966), founder and writer of the Surrealism Manifesto, not only praised his movement, but also explained the reception of other movements that had developed alongside Surrealism. For example, he emphasized the negative reception of Cubism in France. Some like the art critic Paul Valery (1871-1945) argued that it was impossible to distinguish on a canvas the style of a Cubist from another Cubist. In a sense, in this chronological chapter, Breton sustained that Cubism indeed tore the artist’s stylistic individuality. In the end, he explained the Futurist awakening alongside its manifesto, where it was made clear that a dynamic moment could no longer be painted in a representational way because the work itself had to emanate dynamism.

Jean Arp (1887-1966) and Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), on the other hand, focused their chapters on Abstract art. They argued that in the Renaissance artists were encouraged to use reason, but that in the 1940s, this priority no longer made sense, especially with the eruption of the world wars. According to them, instead, Abstract art was meant to be a “natural” and “healthy” art because it encouraged people and artists to let unrestrained inspiration emerge For example they wrote that if on the one hand the realistic landscape focuses on details – such as the accuracy of the trees -the Abstract landscape communicates the atmosphere with the tones of the colors, involving the spectators in the scene, rather than limiting them by making them distant observers of the landscape.

The catalogue testifies to the desire that Peggy had to bring to America and represent the movements of the artistic avant-garde, without choosing to stand for one only in particular. This approach is evident in the construction of the two rooms of the Art of This Century gallery: one was dedicated to Surrealist art and the other to Abstract art. The combination of these two rooms increased Peggy Guggenheim’s reputation.

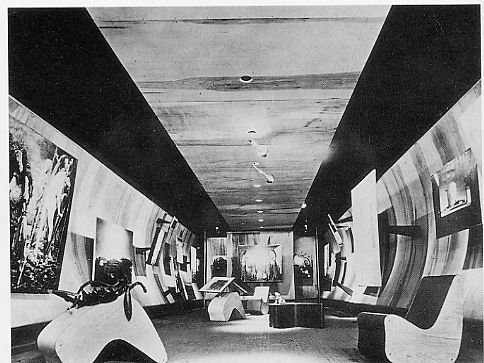

The Surrealist gallery was entirely clad with concave wooden plates, creating a bubble detached from the outside world. The works were not hung on the walls in a traditional way, but rather suspended from cones positioned in a random way. In addition, Keisler created a very extensive network of electrical cables, so that each work could be illuminated casually and alternately every thirty seconds. We can imagine this randomness, a Surrealist founding concept, declined in every single element of the room, echoing Wagner’s concept of Gesamtkunstwerk: a “total work of art”. Inside the room we find artists such as Alberto Giacometti, Joan Mirò, Marc Chagall, Salvador Dalì, Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst, whom Peggy helped financially during the war years.

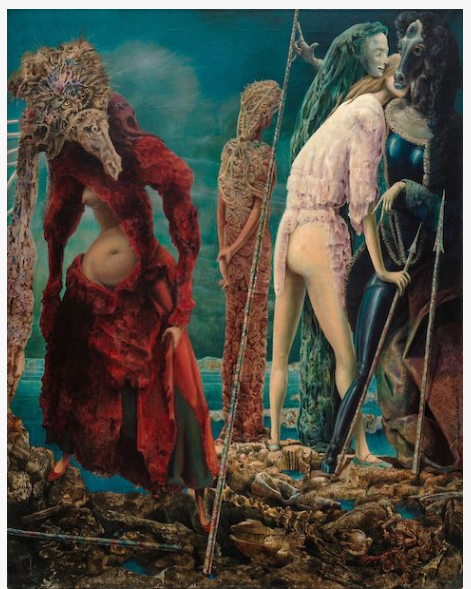

In this room, Ernst’s Antipope (1941) was exhibited. This painting testifies the expression of Ernst’s emotional unconscious, who at that time had a love affair outside of marriage with Peggy. She is wearing the red dress, while the green woman looking intensely at Ernst on the right represents his lover. The spear dividing the paiting symbolizes the distance between the couple,

The Abstract gallery had blue walls and a purple floor, because Peggy liked colors. The paintings were not hung on the wall, nor suspended from cones. Kiesler under Peggy’s supervision decided to further challenge academic tradition by suspending the paintings in the center of the room, so that visitors could see the works at three hundred and sixty degrees, and thus could contribute to the atmosphere created by the painting. They were exhibited unframed, changing the visitor’s perception of the validity of a work of art – is an unframed painting considered a validated painting? Does it require the same respect as to traditional paintings?

Here we find works by Kazimir Malevič, El Lissitzky, Nikolaus Pevsner, Jan Arp and also Piet Mondrian, whose works are still exhibited at the Guggenheim in Venice. Mondrian’s Ocean 5 (1915) inherits the influence of Cubism, not only from the oval shape of the canvas, but also from the way the landscape is executed. Sea waves are determined by their structure rather than their realistic representation.

This gallery partially explains the artistic variety present today at the Guggenheim in Venice. Peggy was attracted to the movements of modern times, and what makes her such an atypical collector is the fact that she had chosen to exhibit many of them. Art of This Century was closed in 1947, and a year later Peggy came to Venice and curated the Greek Pavilion of the Venice Biennale. In 1949, she settled in Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, the current Peggy Guggenheim museum.

The Peggy Guggenheim Collection, located in what used to be Peggy’s house and gallery in Venice, is running the crowdfunding campaign “Together for the PGC” so to keep its collection and didactic activities open despite the COVID-19 crisis. Any type of contribution is warmly welcomed: https://www.guggenheim-venice.it/en/support-us/donate/