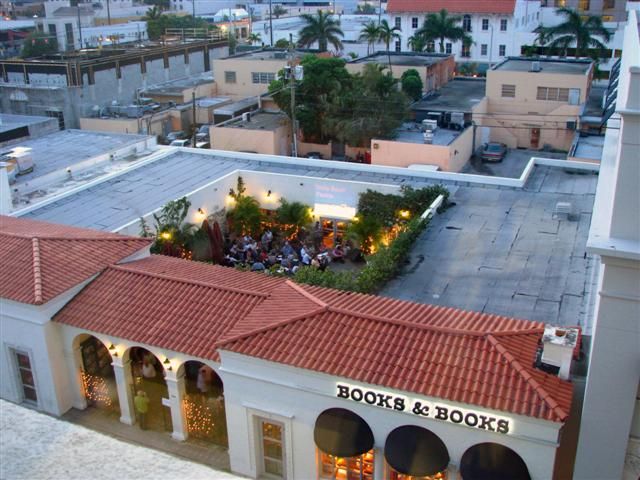

There is a bookstore in Miami tucked into the heart of Coral Gables, a suburbia-esque neighbourhood just outside of downtown. Walking through the gated archway to Books & Books (an apt name), one finds themselves immersed in a charming Spanish courtyard, encircled by three wings, and through the doors to each wing, shelves filled to the brim with a seemingly endless assortment of books. The experience is mesmerising for any bibliophile, but also disorienting. With so many titles, how is it possible to choose just one? Such was my affliction during my last visit.

A view of Books & Books in Coral Gables, Florida

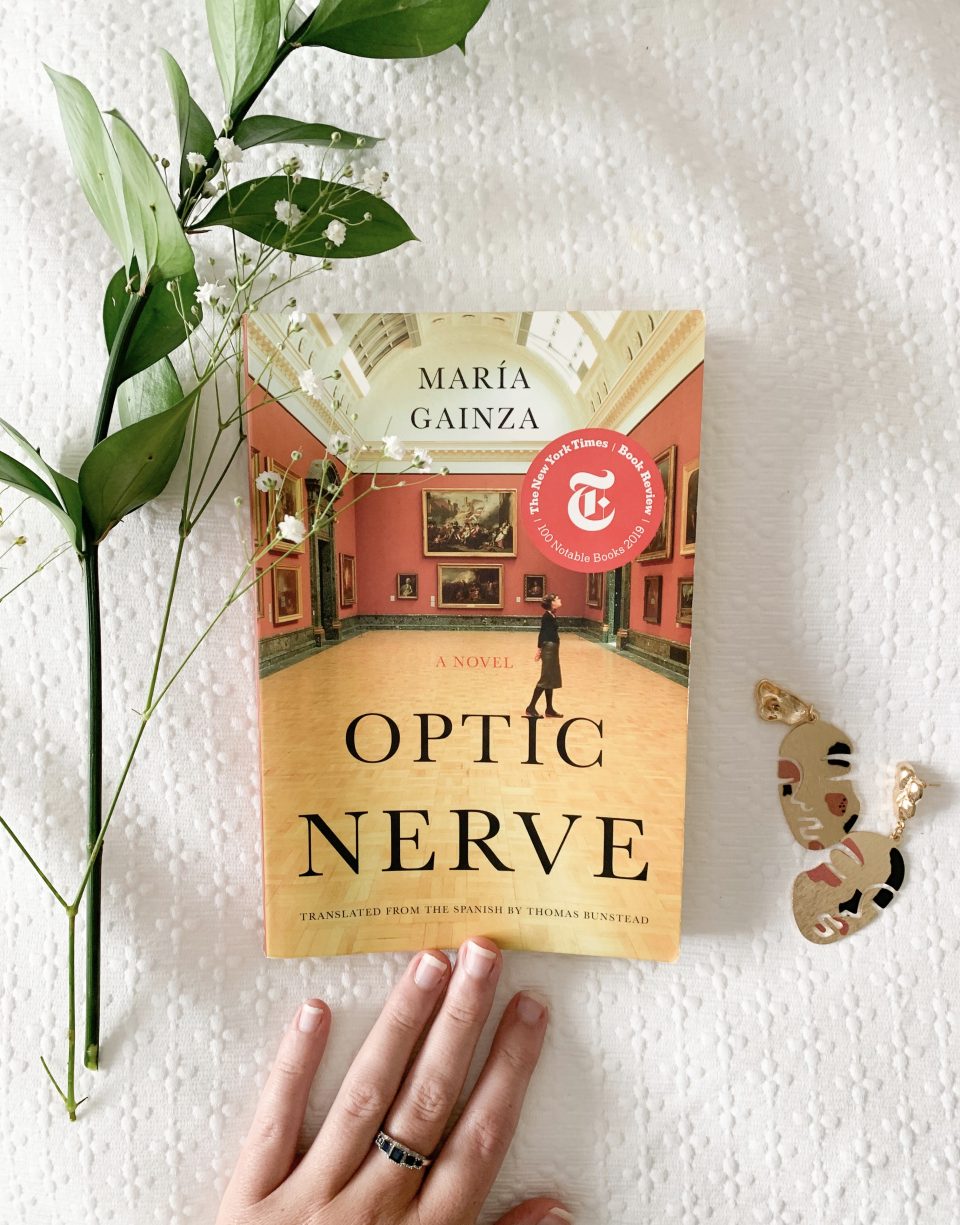

I must have spent nearly two hours perusing the shelves, and was very near to giving up, when a cover caught my eye. Optic Nerve, it read. A woman stands in a gallery, staring up at an unseen painting. Sunlight streams in through the skylights, and a cheerful warmth is palpable in the room, compounded by the burnt Sienna shade chosen for the walls. However, the warmth is starkly contrasted by the woman. She is dressed in all black, her hands behind her back. Her stance and blurred figure give the impression that she, too, has just been perusing, searching, and like myself, has found something that has given her, as María Gainza puts it, a “beautiful shock”. Though, her face is not one of delight, but of deep contemplation.

The first line of the synopsis printed on the back cover goes like this: “The narrator of Optic Nerve is an Argentinian woman whose obsession is art.” Upon seeing the words “obsession” and “art”, I didn’t even bother reading the rest. I snatched it up greedily and made my way to the cash register. It was the only book I purchased that day.

It was in the room entirely devoted to art literature that I found that novel, which has forever changed the way I look at and perceive art. María Gainza’s Optic Nerve is not only a triumph, but also essential reading for any art lover.

I include this anecdote of the day I bought the book in Miami because Optic Nerve is itself an anecdote of dizzying detail (no small feat for a novel less than 200 pages long). It is part autobiography, part art-historical narrative, and part jarring fiction, belonging to the blurry literary category of autofiction. For it is jarring, each chapter demands to be digested—one has to look away. Part of Gainza’s genius is this unsettling feeling that she leaves with every finished paragraph. She reveals to us that when we are reading the book or looking at an art piece or understanding the historical background of a long since dead artist, we are in fact looking at ourselves. For, in Gainza’s words, “Isn’t all artwork—or all decent art— a mirror?”

She uses the term “sui generis” to describe El Greco, especially after his move to Toledo in 1577. Sui generis is generally used in biological terms, however in this instance we take the literal meaning: of its/his/her/their own kind, in a class by itself, and therefore “unique”. The Merriam-Webster dictionary adds another synonym for the phrase: “peculiar”. In Optic Nerve, this phrase not only applies to El Greco, but to every person that touches her life, artist and non-artist, and even to herself. The individuality of how different people experience art is meditated upon and celebrated, and going further than this, the experience of life itself is examined and dissected with regard to its nuances and ironies in each singular person.

In one such meditation, we find that her cousin, also named María, finds solace in the waves at Mar Del Plata, collaging the walls of every corner of her room in shades of green and blue. She finds peace in the unlikely Gustave Courbet, specifically The Stormy Sea, Mer orageuse, before losing herself, and her life, entirely. Her collages are gone with her— no explanation to ease the pain. In the same way, Gainza reflects on the life of Rothko. Like the cousin, he finds solace in colour, though for Rothko, it was not in the cool tones of the ocean waves. Red, for him, was the shade of light. Gainza quotes him as he tells his doorman, “There’s only one thing I need to take care of: stopping the black from swallowing the red.” It was a struggle he continued to fight through his art for the rest of his life. And perhaps he won in this, as “when the police arrived, the puddle [of blood] had become a pool of red—about the same size as one of his paintings”. Like cousin María, Rothko also “took with him certain secrets”. Thus, María Gainza finds that we can postulate long hours about others, about the souls of those with whom we share this earth, yet we will never find all the answers we crave, as each of us is sui generis— of our own.

Optic Nerve ponders countless people, from Alfred de Dreux to her cancer-ridden husband, Tsuguharu Fujita and her ex-best friend Alexia, to Augusto Schiavoni and her estranged half-brother. And in all of these, she finds pieces of them, and pieces of herself, but can never quite see the full picture. This realisation prompts her to exclaim in frustration, “I don’t know what it is I go looking for.” And as such, don’t we all come to this conclusion? When looking at art and people, we look for refractions of ourselves, but when we can only catch glimpses, we are unsatisfied, and even more so when we find nothing. This is not to say, however, that this is fruitless. Finding art in our lives is a constant effort, a constant battle to see everything, to strain to capture every detail, in light and dark. As María Gainza reminds the reader in Optic Nerve, “it is possible to predict one’s fate”. We will eventually be lost to oblivion, like Courbet, like her cousin María, like Rothko, and all other lives that manage to touch our own, artists and loved ones alike.

One of the last lines in the novel goes “A quiet joy comes over me as my feet touch the ground, poetic joy, I think they call it.” This is what we go searching for, in the end, more so than reflections of ourselves. As I closed the book after finishing it and gazed at the cover once more, I found my view had changed of the woman looking up in the gallery. She is not sombre, but indeed has found this poetic joy that we search for in our lives and in art. I’m not sure myself that I have found it yet, but I’m going to keep looking— as do we all.

Yeh, keep looking – that’s all we have to do! 🙂 Sounds like a great read!

We’ll find it eventually! 😉

This review in and of itself is a stunning piece of literature, thank you!

I cannot tell you how much I appreciate that. Thank YOU! 😁