Hidden in a side street in the city centre, far from the main touristic hotspots, the Boschi Di Stefano Museum-Home is well worth a visit despite the minor coverage it is reserved among the local art scene in Milan. This institution greatly differs from the other museums featured in the previous #MuseumHighlights, as its collection is hosted in a musem-home and is therefore relatively smaller. Nonetheless, the museum is rich in masterpieces that, as gallery intern, I have had the privilege of examining in detail as I attended a private viewing of the display. The guide I am here to compile is therefore not a list of underrated or unknown pieces from an ample national collection like that of the Rijksmuseum for example. My article rather aims to present a limited selection of significant works within the Boschi-Di Stefano collection, in order to illustrate the Milanese collecting taste during the first half of the 20th century and showcase the close relationship the collectors developed with the artists.

On the second floor of a quintessentially 1930s building, designed by Piero Portaluppi under the commission of Francesco Di Stefano, is located the museum-home, within the former flat of Marieda Di Stefano and Antonio Boschi. The couple inherited the father’s art collection and continued building upon it with new acquisitions until the end of the 1960s. After the collectors’ passing, a total of 2000 artworks was entirely donated to the Municipality of Milan, according to Antonio’s will of exhibiting the collection in a freely-accessible space for all citizens. From the overly-filled, bizarre and ever-changing wunderkammer, the curators selected around 300 pieces to be displayed in chronological order within the former flat, which maintained some of the original features and was decorated with contemporary furniture from the 1930s. Upon entering the museum-home, I was greatly intrigued by the spaces’ atmosphere and had the impression of visiting the “house of an art collection” more than that of its collectors, with the artworks crowding the walls and arranged throughout the different living spaces without labels or explanatory panels. Creating a minimal selection of highlights was no easy task and personal taste did definitely play a role in the process; nonetheless, it is hoped that it will provide an insightful introduction to such a wide-ranging collection of the Italian Novecento art.

After the first few rooms showcasing the artists belonging to the early 20th century Novecento Italiano movement, the former study room is now entirely dedicated to Mario Sironi. The collectors established a close personal and professional relationship with the artist, acting as patrons and helping the young Sironi consolidate his presence in the local and national art scene. As such, the fifth room of the display explores the span of his artistic career, through a selection of 30 paintings that illustrate the different phases in his stylistic development. To further underline the monographic quality of the room, the paintings are flanked by furniture decors that Sironi himself designed for the 1936 Triennale. Among these, the artwork I selected, Venus of Harbours (1919, tempera collage on canvas) significantly demonstrates the artist’s major turning point, from the previous futurist and metaphysical style to a newly reached “formal synthesis”. The artwork dominates the central part of the main wall, surrounded by examples of the preceding metaphysical experiments (Mannequin, Composition and Apparition) precisely to mark the different formal choices. The figure of Venus, still showcasing metaphysical residues in her monumental, mannequin-like forms, stands out against a harbour urban setting, evident in the ship going out to sea. Distortedly depicted in the same scale as the Venus, in the right corner is a skyscraper, made with a newspaper cut-out. Behind it departs a street with tracks in which a tram is passing, hereby introducing a leitmotif in Sironi’s art, that of the suburbs and its attached connotations of melancholy, misery and alienation. The painting was dated to 1919 thanks to the collage insertion of a newspaper cutout and stands cohesively among the Novecento Italiano movement’s works. A mature, consolidated style, Sironi’s formal synthesis was in fact characterised by an “aspiration towards the tangible, the simple, the definitive” and “more solid, wider and stronger constructions, in line with the great tradition of local Italian art”. This can be witnessed in the Venus, through the plastic, almost Cubist-like definition of forms and landscape, using a simple, reduced palette of dark colours to convey the scene’s mood alongside the use of different types of paper. Shapes are simplified to the extreme, thus providing almost anonymity to the figures, perhaps in the aim of favouring identification. The modern goddess of the Venus comes therefore to represent the transition from a rigid concept of womanliness to a freer awareness of her power and body.

Radically different in colour and style is the second highlight, Renato Birolli’s Eldorado (1935, oil on canvas), located in the former dining room, in which the artistic taste of the Boschi-Di Stefano couple is fully displayed. The painting is a formal exercise, through which a new vision of the urban suburbs can be imagined, strongly in contrast with Sironi’s gloomy cityscapes. The setting for the Eldorado is a peripheral Milan, where city and countryside still blend. Here working class people can get away from work to enjoy a beach resort and freshen up in the insalubrious water of the river Lambro. Echoing Giorgione’s The Tempest and Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, the painting’s foreground depicts a lush and vaguely exotic nature, where a group of naked people is idling about. Synthesising French modernity, the scene is painted in a Van Gogh style with references to Cézanne, using dazzling colours and fervid brushstrokes to convey the possibility of finding happiness and beauty even in a miserable situation. In the 1930s, Birolli gets back to a spontaneous expressionist style whose outcomes are radically far from the Novecento style and will contribute to the renovation of Italian art. In regard to the wider European culture, his urban narratives seem like a pictorial projection of the contemporary poetic realism of French cinema. The theme of the Eldorado, myth of a lost world, was popular among the Hermetic poets writing in Milan and its echo can also be perceived in other paintings by Birolli, Great Female Mistics and The Chaos II.

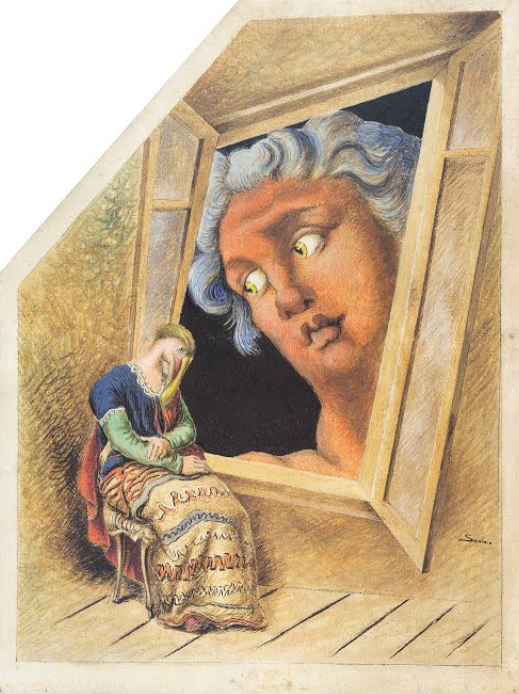

Next, we have the collection’s iconic work, also depicted in the museum-home’s logo: Alberto Savinio’s Annunciation (1932, oil on canvas). The work belongs to a series of portraits with bird heads painted by the artist since 1930. Here Savinio mixes periods, places and genres driven by a childlike curiosity and wonder. He reinterprets the Christian theme of the Annunciation: a pelican-headed Madonna – in Christian iconography the pelican symbolises goodness and maternal love – is sitting next to a lopsided window, metaphor for the openness towards the unknown, the unexpected, towards imagination. Outside is the huge face of the angel, drawn in a classicizing style, his figure too big to enter the room just like the mystery he is announcing, too great to be understood by Mary. The ironical metamorphosis of humans into animals is closely linked to the Surrealist movement and is here presented in an even more original manner through the unusual shape of the canvas, that alters the traditional perceptive system of the painting. The work was acquired by Francesco Di Stefano, Marieda’s father, at the artist’s solo exhibit in 1933 at the art gallery Galleria Milano.

It is in the former study of Antonio Boschi (room 9) that begins “the fullest and most exciting period for the collection, in which the collectors [Marieda and Antonio] synergically collaborate with the artists that were visiting their home in the postwar period”. This phase is introduced in the display by a monographic room on Lucio Fontana featuring an extraordinary anthology of works from the 1950s. To represent the “Holes” phase that caused a scandal for Fontana’s career I have chosen Spatial Concept (Crucifixion), a mixed technique on chipboard artwork from 1956. Its variously coated colour surface features approximate geometrical shapes alongside a stark colour contrast. Unlike other Spatial Concepts that feature lighter background colours and a softer distribution of holes and fragments, the Crucifixion presents the sudden impact of an explosion of colour onto the canvas. Fontana’s gestural actions, the “holes” and “slashes”, are indeed often combined with a chromatic substance that is dense, three-dimensional, almost in relief. As a result, the formed structures in Crucifixion seem to hover about in sidereal spaces. To give solidity and fullness to the artworks, Fontana, who had started his career as sculptor, also makes use of coloured glass fragments distributed on the work’s surface. In this specific artwork, the fragments are so dark that they almost merge with the canvas. Fontana was the founder of the Spatialism movement, whose aim was not to impose a “figurative theme” to the observer, but rather to allow the viewer to be in a condition “to autonomously create it, through the fantasy and emotions of the person receiving the artwork. A new awareness is forming among humankind; therefore, it is not necessary to depict a man, a house, or nature anymore. Instead, one should create spatial sensations with his own imagination”. These theoretical concepts can all be verified and better understood when observing any of the works featured in this room. A close friend and collaborator of the Boschi-Di Stefano couple, Fontana was one of the most prominent driving forces behind the lively Milanese artistic experimentation that would audaciously confront the international art scene.

Last (in chronological order) but not least is the artwork Atomized Landscape by Enrico Baj (1957, oil and fabric collage on canvas). Located in the former study of Marieda Di Stefano (room 10), the piece is a prominent example of nuclear art, an artistic movement founded in the second half of the 20th century by Baj himself and Sergio Dangelo. In the movement’s manifesto they describe the disintegration of forms at the time of the atomic universe, when “the forces are electronic charges” and “ideal beauty coincides with the depiction of the nuclear man and of his space”. The works’ titles in this room all echo the mindset of those Cold War years, reflecting the widespread fear surrounding nuclear fallout and the atomic bomb. An akin energy can in fact be found in the title of Baj’s painting, Atomized Landscape. The work belongs to the artist’s Informal phase that makes use of a wide range of materials, as in the series “Mountains”, which includes Atomized Landscape, Character in the mountain (ca. 1958) and Agitate, stones and mountains! (ca. 1938). These works are linked with the early period of Italian Neo-Dada, evident in the addition of cut-out wallpaper. In Atomized Landscape, abstract shapes and sprays of colour outline a desolate landscape, depicted as in the case of a nuclear accident according to collective imagination. Colour is also crucial in dictating the atmosphere of the painting, with earth tones dominating in the landscape’s depiction and a vibrant, almost radioactive hue of green for the sky.

The Boschi-Di Stefano Museum-Home holds the legacy of 20th century Italian (especially Milanese) art, showcasing a great range of artists and movements which have had a strong influence upon future artistic developments. Hopefully this article will have enticed you to visit this unique art institution, whose significance relies not only in the artworks it exhibits but also in the original decors and the vibrant feel of the collectors’ onetime living spaces. You can read more about the museum and its collection on the website: https://casemuseo.it/project/boschi-di-stefano/ as well as on the museum foundation’s website: http://www.fondazioneboschidistefano.it/ws/en/. If you are keen on an online visit, the Boschi Di Stefano Museum-Home has partnered with Google Arts&Culture to offer a virtual exhibition experience, with several close-up images of the artworks as well as specific thematic folders. The resource is available here: https://artsandculture.google.com/partner/boschi-di-stefano-museum-home?hl=it