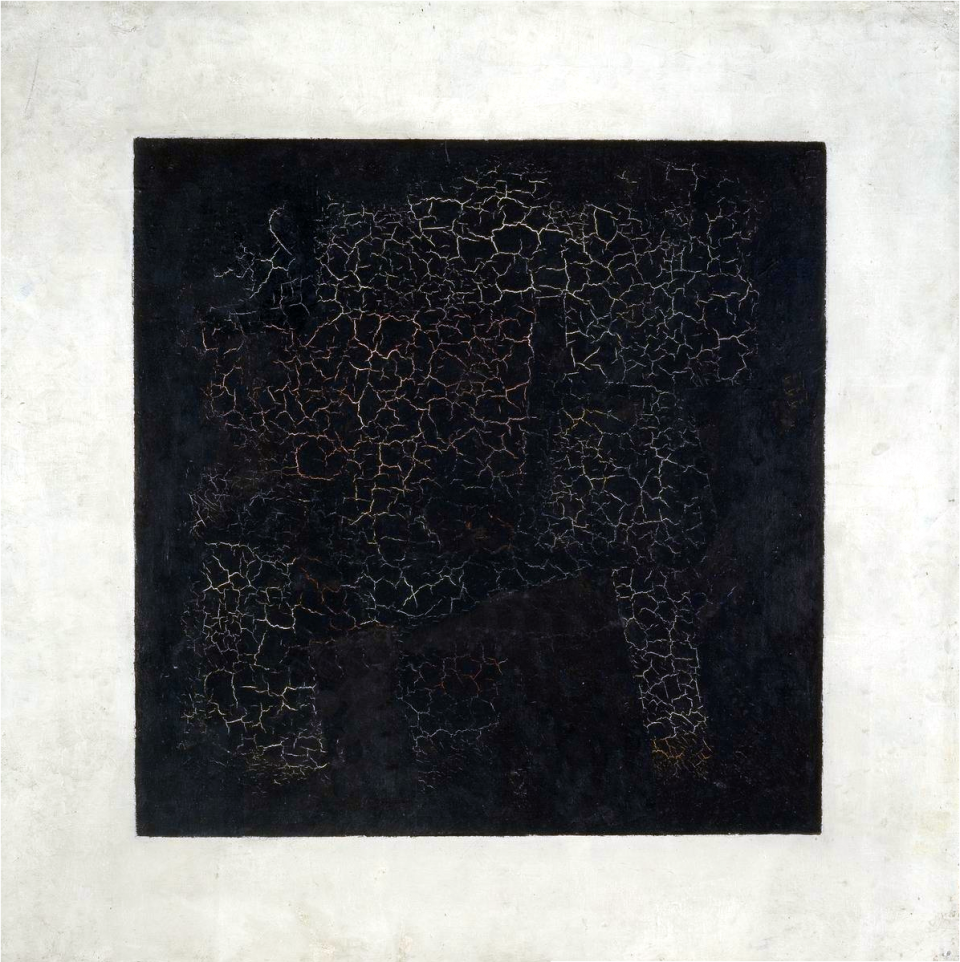

The objet d’art which preoccupies the art historian’s focus, upon which she labours and which she inscribes with her desire is a kind of living dead, a not not-present entity which in its indecipherable radical alterity stubbornly persists in effecting our present day, while at the same time properly belonging to an entirely different, and irretrievably lost, world. In psychoanalytic terms, we might say that this ‘thing’ which we pour over in art history is a partial object – one which is ‘dumb’ (dependent and derived – here we might say on the sociocultural context, the artist’s efforts etc.) but one which simultaneously seems to have a mind and a subjectivity of its own, an impossible part-objective and part-subjective entity that engages all who gaze upon it individually.

In any case, its ontological status (i.e. the status of its existential being in the world) seems to be ambiguous, constitutively ephemeral and difficult to capture – hence the oft-used metaphors of ‘mirrors’ and ‘reflections’ when speaking of the phenomenal effect is holds over us. Not merely that, once viewed from the prism of art historical study, the artwork’s immanent contradictory character which makes say a renaissance painting appear so as to be perceived by one as an uncanny remnant of a space and time that’s long gone, a kind of portal on the one hand, and on the other as a spectral presence that continues to haunt our present imagination, the artwork and its aura become all the more disquieting. This doubly-facing sense of a perfect encapsulation of time and its ultimate final irrecoverability which emanates from the artwork forms the foundation for the assertion that the art historical discipline is itself a melancholy art wherein our attempts to conjure up, present and approximate the art object actually end up alienating it – at first through language (linguistic narration), then by way of historicizing (setting it in a context disparate from our own). The repeated failure to think through, digest and express in writing this strange function of the artwork then has the effect of producing in its observers and writers a peculiar and even pathological obsessional fixation on the irretrievable loss of an imagined object that we so desperately wish to bring in from the ‘far’ into the ‘near’ – thus generating melancholia as the complex of unresolved grief and mourning.

Why am I saying all this? I was prompted in my reflection by Rose Berry’s latest piece on the novel Optic Nerve in which she pays particular attention to the trope of art as a mirror. As a counter to this particularly persuasive positive mental image of art as a revelatory phenomenon, one which brings out some essential truth about ourselves, discarding by way of paint, stone or practice the layers of ideology, bias and pretence that society has enforced on us, the writers of a melancholy art history seem to suggest a different way – on this alternative understanding of art and art history espoused by the likes of Michael Ann Holly in ‘The Melancholy Art’, the artwork actively creates the impossible objects of our desire that ideology mistakenly attempts to get at, and further, has the artwork itself act as the propeller of the practice of writing art history, as if this compulsion were a drive played out at the level of our subconscious. These art historians argue that there is another, more ambivalent way of looking at and understanding art where the artwork presents itself as an obscured subterranean tunnel which whizzes right past both the imaginary and symbolic registers of our subjective identification upon whose institutions, morals, and (stupid) wisdoms we construe the selves of our waking existence.

Within this imaginative conceptual framework, is it not the case that instead of bringing to light our own self-fashioned, presentable and representative images of ourselves which would somehow make explicit the implicit aspects of our personality, the artwork in actuality serves moreso as a receptacle of our interiority in all its problematic dimensions, always deeply immersed in mourning for a past (always imagined) state of harmony and pure enjoyment?

Rather than aiming at completion and reconciliation, I would wager that this mysterious and forcefully attractive aura of the art piece works to disrupt and disquiet, stirring a deep sense of loss and absence which is as yet outside the realm of language and outwith our ability to articulate it.

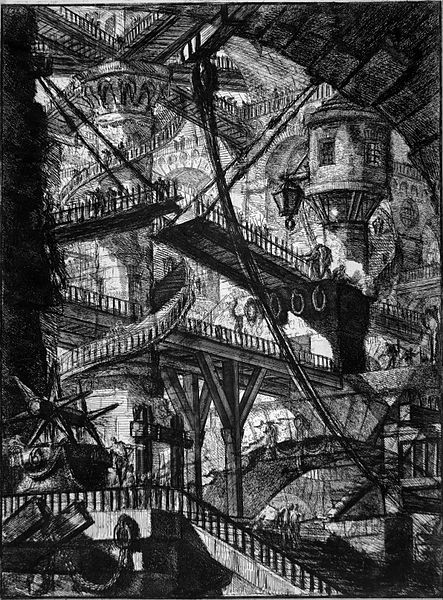

Lastly, it’d be wrong of us to forget to mention the fact here that art history as a discipline with its own objects of inquiry possesses certain moods – ‘mood’ here describing the fundamental attunement to the world of the art historical partial object. This question of mood which often gets neglected in theoretical discourse may be vindicated in the least bit by the realization that academically published pieces on the topic of art history must also bear the marks of the particular moods and psychical tinctures of their authors. My contention as regards the importance of mood in connection with the art piece and the practice of art historical writing would merely be that apart from an ever-present, didactic matter-of-factness, or a positive revelatory mood, art history too has its negative openness to contradiction and incertitude on a modal register perhaps best encapsulated by the Wagnerian notion of the ‘night of the world’ – instead of bringing to surface, the art object estranged from its proper place in history unearths a fatal profundity which envelops us in its immensity and whose aesthetic revelations do not flatter our ego ideal.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Carceri, 1745, Kupferstichkabinett Dresden, in public domain.

When pondering the art historical object, one should brace oneself for an inevitable sesnse of disappointment that accompanies any confrontation with feelings of grief to do with the artwork’s impermanence – expecting that the object will wither and lose its brilliance despite the best efforts of conservators and archivists – or with grief of yet another kind that is tied to the knowledge of one’s inability to ever comprehend the object’s true meaning and significance as when it was received at the time of its creation.

What I ask then, is that we merely consider the very real possibility that the discipline of art history along with its objects of study is mired in a resolutely mournful vocabulary.