Britain’s fraught history of imperial conquest, displacement, cultural whitewashing and enslavement will perpetually haunt the pseudo-patriotism surrounding a great ‘British Art’ as long as these issues go unaddressed. As per the astute Stuart Hall observation, the humble and quintessential British cup of tea is in itself an excellent example of the fallacy of a truly ‘British’ production. As the prominent cultural theorist explains, the shared cultural exchange of tea drinking directly stems from violent disruption and overruling of overseas dominions; the tea leaves stem from voyages to India while the sugar derives from cane plantations in the Caribbean. The profit from the exchange of goods and people is no anachronistic notion – Britain consumes Black culture en-mass whether it be music, sports, film and television, food etc. The art world is, historically and presently, extremely White, wealthy and male – Britain is a gleaming example of this.

This is an issue rooted in a history of problematic gatekeeping and access. With non-white people making up less than 1% of Britain’s population in 1950, the prevalence of Black individuals in elite environments like art schools, museum walls and auction houses was even lower. Some of the first noted Black artists in the UK hail from the Windrush generation – the moniker given to a generation spanning 20 years whereby people from the commonwealth nations in the Americas, Africa and Asia were encouraged to emigrate and thus rebuild Britain’s economy and landscape post-WWII. Artists such as Frank Bowling, Aubrey Williams and Tam Joseph proved essential components of the progression of art in Britain. Sadly, their acclaim remains retrospective in most cases. A reluctance at the time to acknowledge artists born outside of the UK as making ‘British Art’ proved damaging as these artists would more often find themselves organising their own exhibition spaces outside of mainstream gallery support, financial and otherwise.

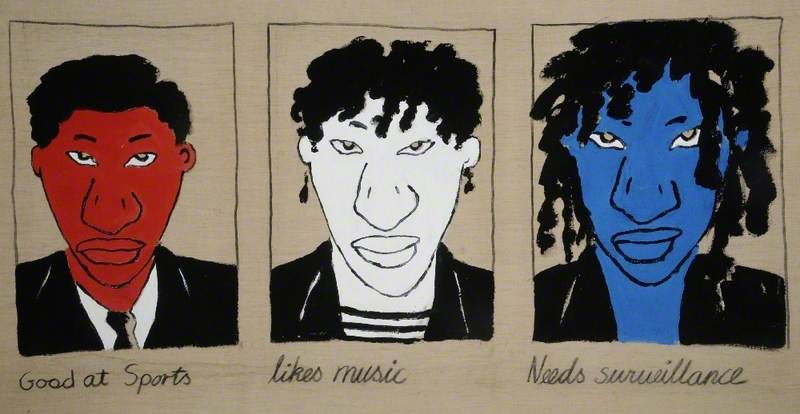

Tam Joseph was and remains an artist constantly overlooked. His work refutes pigeon-holing and simplification far too often ascribed to Black Artists in the UK. He does not acquiesce to generalised presumptions on what it means to make a so called ‘Black Art’ with a praxis stretching across mediums, landscapes, geographies, and subject matters. Among his most celebrated works is School Report, a scathing look at the systematic racism in the UK education system whereby Black and ethnic minority students become profiled mugshots inflicted with a constant stream of oppression from microaggressions to more overt prejudices. Joseph links the failing school system to British society at large – the red, white, and blue used for the faces of each student alludes to the larger powers at work in the erasure of Black bodies from the concept of ‘Britishness’ and patriotism.

Frank Bowling is another artist failed by the British art world in terms of access to spaces deserved. A classmate of the celebrity status White Artists David Hockey, both studied at the RCA though Bowling found himself constantly regarded as a ‘Caribbean Artist’. This resulted in exclusions and limited gallery representation in London, causing a relocation across the pond to New York. Bowling found New York a city more adept and comfortable with exhibiting Black artists (it was here he eventually gained the Guggenheim fellowship twice, exhibited widely and performed well at auction).. The work Who’s Afraid of Barney Newman from 1967 exemplifies the artist’s vanguard practice in subverting the curator of the day’s dogmatic stratification. Referencing noted White Abstract Expressionist Barnett Newman’s ‘zip’ paintings, the piece composes intense colour fields of red and green separated by a ‘zip’ of yellow, while the outlined maps of South America and Guyana remain a stain on the work. White ab-ex artists like Newman were afforded the luxury of making abstract art without having their race and identity brought upon every interpretation of their work. Bowling references his native Guyana, a country recently independent from British colonial rule at the time, while further referencing the colours of African liberation – addressing the complexity and multifaceted nature of the African diaspora in the Americas. The work functions on many levels and defies one-note, lazy denotations.

Frank Bowling’s recognition in Britain was extremely delayed – the artist’s first retrospective took place at Tate Britain only last year – nearly 50 years after most of the paintings shown had been produced. This hindsight favour reflects Britain’s lacklustre progression in curatorial and collecting practice in major institutions. The Tate – the primary art collection and institution in the UK – first collected a work by a Black Artist in only 1985 with Sonia Boyce’s Missionary Position (also only the 5th work by a woman in their collection). The RA first elected a Black artist as an academician in 2005 (Frank Bowling) and Lubaina Himid was the first Black woman to win the Turner Prize as recent as 2017. Curatorial activism is slowly emerging in the UK with more shows focusing primarily on Black Artists as centre as opposed to addendum and footnotes on the history of art. Sonia Boyce has been chosen to represent the UK by showing at the British Pavilion in the Venice Biennale next year – the first Black British Woman chosen for this position. Shows focusing on Black Artists primarily such as Soul of a Nation where the Tate Modern collaborated with the Studio Museum in Harlem show promise also. One must consider however the problematic line often skirted by those in the museum boardrooms whereby non-White artists get thrust into the limelight in tokenistic practices of diversifying public image while directors, curators and registrars remain overwhelmingly White. Larger shifts in the entire museum complex must be undertaken, along with a re-evaluation of the history of art and heralded figures propounded in educational institutions and museums.