The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam is well worth a visit just to see Vermeer’s Milkmaid, Hendrik Averkamp’s wintry landscapes, or any of the Rembrandts. It goes without saying that you should take a walk through the Gallery of Honour, which is home to some of the Netherlands’ – and Europe’s – greatest treasures. But I’d like to tell you about the museum’s hidden gems. The advantage of seeking them out is that they are often housed in less popular and therefore less crowded galleries, giving you ample time and space to take them in. In addition, they shed light on different aspects of Dutch history and artistic production, which might be a welcome change if you’ve had somewhat of an overdose of seventeenth-century portraits and still lives. To keep it concise, I’ll only discuss four works, covering a range of mediums and eras, to tempt you to continue for yourself.

Anonymous, Dolls’ house of Petronella Oortman, c. 1686-1710. Credit: Rijksmuseum

Jacob Appel, Dolls’ House of Petronella Oortman, oil on parchment, c. 1710. Credit: Rijksmuseum

First, there is the doll house of Petronella Oortman. This was not a toy for children, but a form of collecting for bourgeois ladies of the Dutch Republic in the seventeenth century. The Protestant wives of wealthy merchants and governors, such as Petronella, were allowed limited distractions. Furnishing a doll house was considered decorous however, as such an object could become a conversation piece and a source of pride and prestige. Every part of the doll house is exquisitely realistic, handcrafted by a French cabinet maker and modelled after the luxurious interiors of the great canal houses in Amsterdam. There are several such doll houses in the collections of Dutch museums, but this particular example is so beautiful that it was painted by Jacob Appel (Dolls’ House of Petronella Oortman, also in possession of the Rijksmuseum) and became the subject of a historic novel by Jessie Burton, The Miniaturist.

Lucas van Leyden, Worship of the Golden Calf, oil on panel c. 1530. Credit: Rijksmuseum

The second highlight is an altar piece by Lucas van Leyden dated to ca. 1530. His most famous painting is The Last Judgement, a similar triptych which is housed in the Lakenhal in Leiden, but The Worship of the Golden Calf is at least as beautiful, and perhaps even more fascinating. It tells the story of how the Israelites ignored God’s command not to worship images or sculptures – a topic which was beloved by Protestants. Its depiction by Van Leyden may have been a signal of the rise of Protestantism in the sixteenth century. Notice particularly the fabric expression, the fantastical landscape and the jewel-like tones of the triptych. Paintings such as this were displayed in churches, but kept closed. They opened on religious holidays to educate the people, but also as a form of celebration, and, perhaps, to offer a glimpse of heaven.

Flower pyramid, De Metaale Pot (attributed to), after Lambertus van Eenhoorn, c. 1692-1700. Credit: Rijksmuseum

The third piece is a ceramic pyramid-shaped tulip vase, attributed to the workshop of De Metaale Pot and dated to 1692-1700. This object reflects several cultural developments, including the Dutch obsession with Chinese porcelain and their efforts to imitate it, the tulip craze, and the influence of the court of William III of Orange and Mary II of England. This type of vase was designed to give each precious flower a place of honour, to emphasize its effect and the number of flowers one could afford. It is a status object because the higher the pyramid, the more flowers it contains, the richer the owner. As stadtholder and consort of the Dutch Republic, and later as king and queen of England and Scotland, William and Mary were important cultural influences. Mary had a passion for flower arrangements and earthenware and became one of the most important patrons of Delft porcelain, notably popularising the pyramid-vase, of which numerous examples are still in the Royal Collections in London.

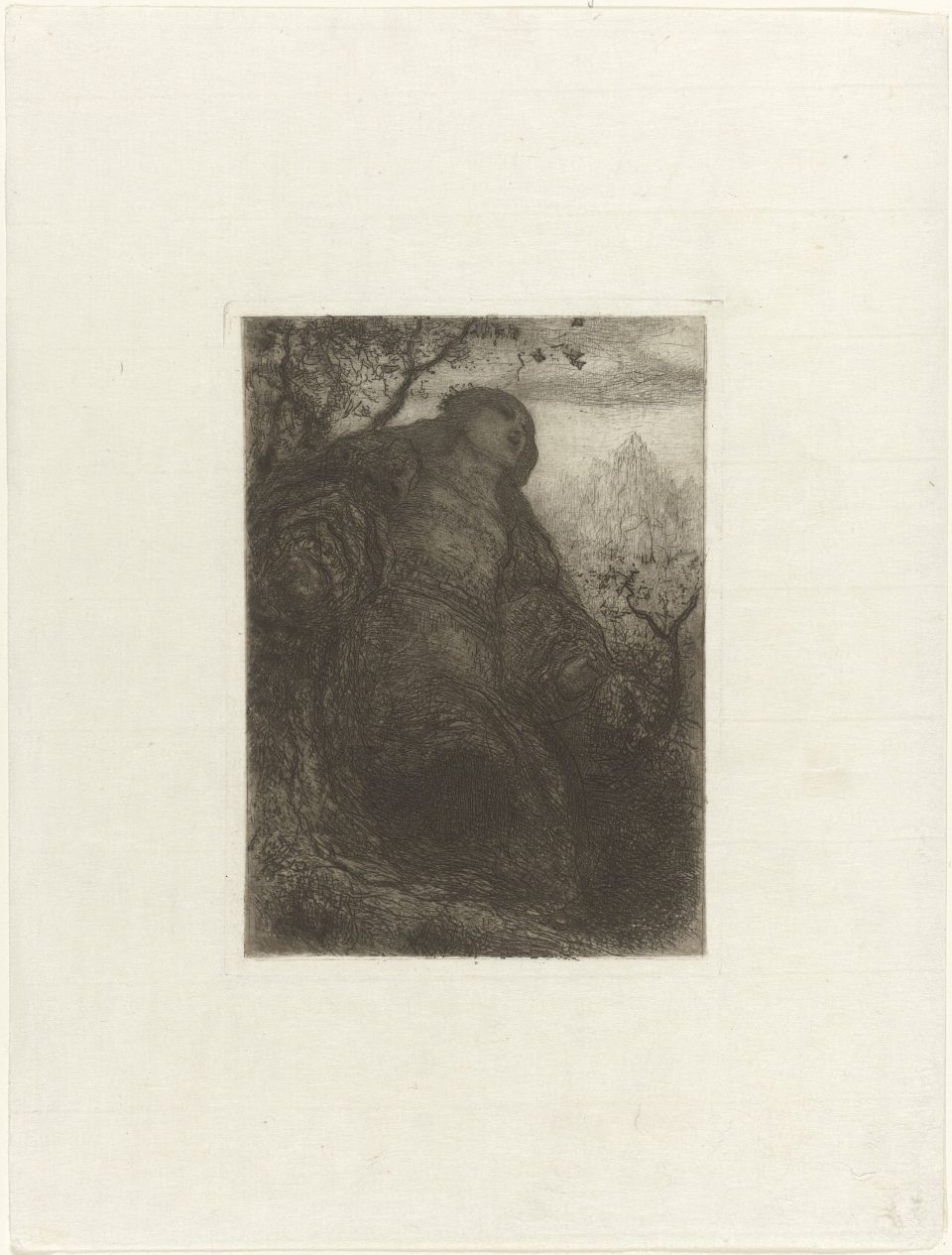

Matthijs Maris, Lady of Shalott, known as ‘Woman under a Tree’, etching, c. 1881-84. Credit: Rijksmuseum

Matthijs Maris, Shepherdess, known as ‘Monumental Conception of Humanity’, oil on canvas, c. 1885-98. Credit: Rijksmuseum

The final piece you should see is Matthijs Maris’ etching Woman under a Tree, (or The Lady of Shallot) from 1881-4. One of the Netherlands’ greatest forgotten painters, Maris was active between the 1860s and the 1910s. His life, like his art, was mysterious. We know little for certain, except that he undertook a life-long search to move away from realism and make ‘immaterial’ works that accurately reflected his inner world. Like many others, he struggled to paint the images in his head exactly how he envisioned them, and would spend several decades retouching some of his paintings. A feeling of melancholy and escapism pervades this drawing, and much of his oeuvre. He often painted fairy tales, or fairy-tale like images, and repeatedly sketched medieval towns with an otherworldly quality. This was common in the nineteenth century but unusual in the Netherlands, and his work did not sell very well. Luckily, his work was preserved in the collections of the Rijksmuseum, allowing new generations to lose themselves in his ethereal world.

There is much more I’d like to share, but the task of recording all the Rijksmuseum’s hidden treasures is Herculean (not to mention highly subjective). However, you don’t need to travel to Amsterdam to start doing so. The Rijksmuseum is well ahead of most national galleries in terms of online resources: it is one of the only museums in the world to not only have fully digitised its collections, but to have made them truly accessible through the Pinterest-like system of Rijsstudio. The website’s various tools can be used for recreation, research and educational purposes, and, now more than ever, for socially-distanced visits to the museum. The virtual museum visit will never truly replace the experience of standing in front of the physical works, but there is at least one advantage. Rijksstudio presents a curated selection of the Rijksmuseum’s collection, just as the physical museum does but, crucially, everything is democratically – horizontally – presented. This forms a stark contrast to the vertical hierarchy in the museum, where the Gallery of Honour and the more ‘crowd-pleasing’ seventeenth-century art is displayed on the first floor, whereas the decorative arts and art from other eras are mostly displayed in the basement and top floors. In Rijksstudio, you are spared the hike through the enormous building, making it easier to seek, and find, its gems.