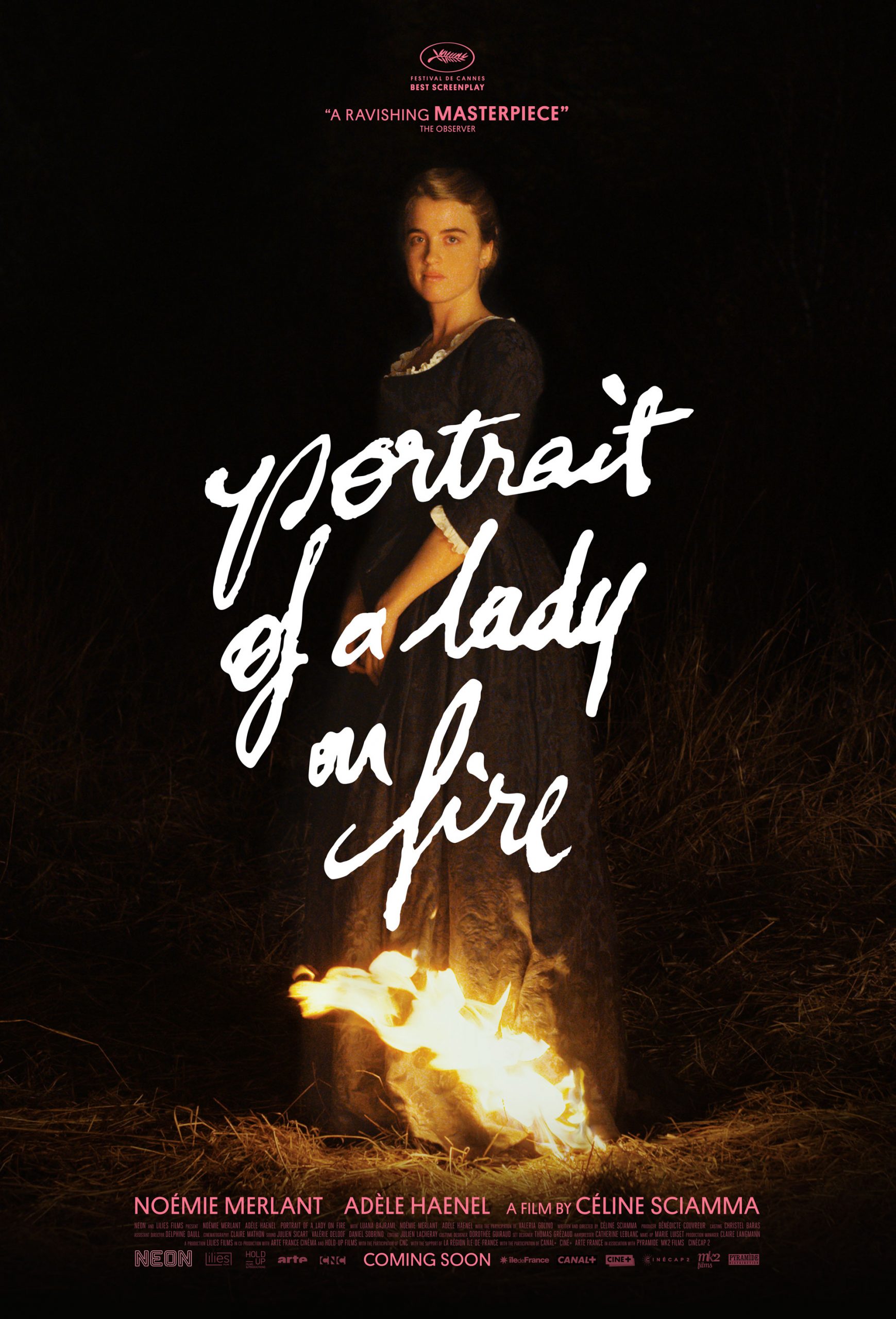

This week dedicated to women in art ends with a focus on contemporary cinema. We present you “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (2019), directed by Céline Sciamma.

According to Sciamma, the cinema is a bourgeoise industry, and as such new characters and new forms of representation are to be sought in order to engage with a young public that is increasingly absent from film theatres. This film perfectly encapsulates the director’s artistic ethics, as it tells the story of Marianne (Noémie Merlant), a young painter that is commissioned the marriage portrait of Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), who refuses to pose for any painter. Marianne is thus hired to secretly portray her, whilst seemingly only keeping Héloïse company. Set at the end of the 19th century in a remote mansion on the Brittany coast, the film presents the slow, subtle development of the main characters’ love, with an (almost) all-female cast. Sciamma realises a powerful (and empowering) portrait of femininity, that culminates in the chorus scene of the village women singing around a bonfire, which evokes witchcraft, power and sorority.

The film is essentially concerned with the gaze, and its related issues. In the first place, the way the director frames the scenes, with an abundance of close-ups that present women as existing in their own right, acts as reversal of the male gaze. Sciamma plays a lot with gazes, reciprocity and point-of-view shots, creating a silent dialogue which reflects the evolution in the protagonists’ sentiment, from insecure interest to reciprocal understanding and desire. Highly significant, and symbolically evoking the whole film, is one scene at the beginning. After verbally presenting and repeatedly mentioning Héloïse and her story, she is finally visually introduced. The suspense and tension build up as we see her, in a point-of-view shot from Marianne’s eyes, captured from behind as she walks covered in a hooded cloak. As she moves, the hood falls down to reveal her blonde hair, her face still hidden. Héloïse then starts running towards the sea and the cliff, seemingly to jump off it. However, at last she turns her head towards us, Marianne and the viewers, fulfilling the desire, which has built up until now, to discover her striking, moving glance that reveals her longing for freedom.

The exceptionally curated music score makes use of classical music to elevate limited key moments in the film, while most scenes are silent. This allows for an even greater focus on the images, on the exchange of glances between Marianne and Héloïse particularly, which occupies a significant part of the film but perfectly renders, without the need for words, their emotional turmoil. The stunning visuals and the warm colour palette function to characterise each woman’s personality and reflect their inner world, creating parallels with natural elements. Tellingly, Héloïse mostly wears blue, bringing the viewer’s mind to the sea, whereas Marianne’s clothes are distinguished by more earthy colours, such as rich reds and oranges, reminiscent of fire. Ultimately, this picture, a love letter to art and feminine creativity, revolves around gaze, to reflect on the way we are observed and how we in turn observe ourselves and others, revealing the tense choreography that this involves.

Have you seen this film? What did you think of it? We’d love to hear about your favourite female auteurs and films! Check out our Instagram stories, over the weekend we’ll be sharing a selection of our (and yours) favourite films directed by women