The outbreak of a plague forces every human being to confront the deeply unsettling issues of death, famine and underserved medical resources. Over time, visual art and literary texts have emerged as the prevailing mediums by which to record or reflect the spread of infectious diseases in contemporary societies.

This painting shows a devastating panorama of the plague, which relates to the outbreak of black death in sixteenth-century Europe.

Credit: Museo del Prado

1. Plague as an apocalypse

The word ‘plague’ derives from the Latin word plaga, which refers to affliction, calamity, evil, and scourge. Since the Middle Ages, the plague has been used metaphorically in literature and visual arts to signify the apocalypse. In the Middle English allegorical poem Piers Plowman (written c. 1370-90) William Langland presented the plague as a divine warning, designed to correct the behaviours of the sinful people living in a morally corrupt society:

“Such as poxes and pestilence, and brought many people to ruin.

So Kind with bodily corruptions killed very many.

Death came driving after him and dashed all to dust.”

(Passus XX, 98-100)

For Langland, the plague represents God’s anger with humanity. This interpretation conveys an apocalyptic vision of plague, portraying the consequent suffering as a sacred punishment.

Credit: British Library

The portrayal of plague as divine punishment of humanity is also evident in visual arts; for example, the iconography of sinners suffering the pain of plague is often used in medieval visual representations of hell, as seen in the image above. The two standing figures are Dante and Virgil, witnessing a group of sinners being afflicted by the disease as punishment. This idea of divine punishment fitting the crime in earthly human society is clearly communicated in this image, which influenced people’s notions of plague during the Middle Ages.

2. Plague as a Mirror

Between 1563 and the Great Plague of 1665-66, London was beset by widespread epidemics, each claiming tens of thousands of lives in this plague-ridden city. At the time, literature and visual arts presented the plague as a reflection of the differentiation of social stratification. The Alchemist (1610) describes a gentleman named Lovewit who is forced by the outbreak of bubonic plague in London to decamp, delegating household authority to a servant in the process:

“Subtle: The master do not trouble us this quarter.

Face: O, fear not him. While there dies one a week

O’the plague, he’s safe from thinking toward London.” (Act I, Scene 1, Line 181-3)

As Cheryl Lynn Ross argues, the English playwright Ben Jonson exemplifies a cruel social phenomenon: once a city is stricken with the plague, people of the dominant social classes flee to their country houses for the duration of the epidemic, leaving the less fortunate in the grip of ‘the Poor’s Plague’.

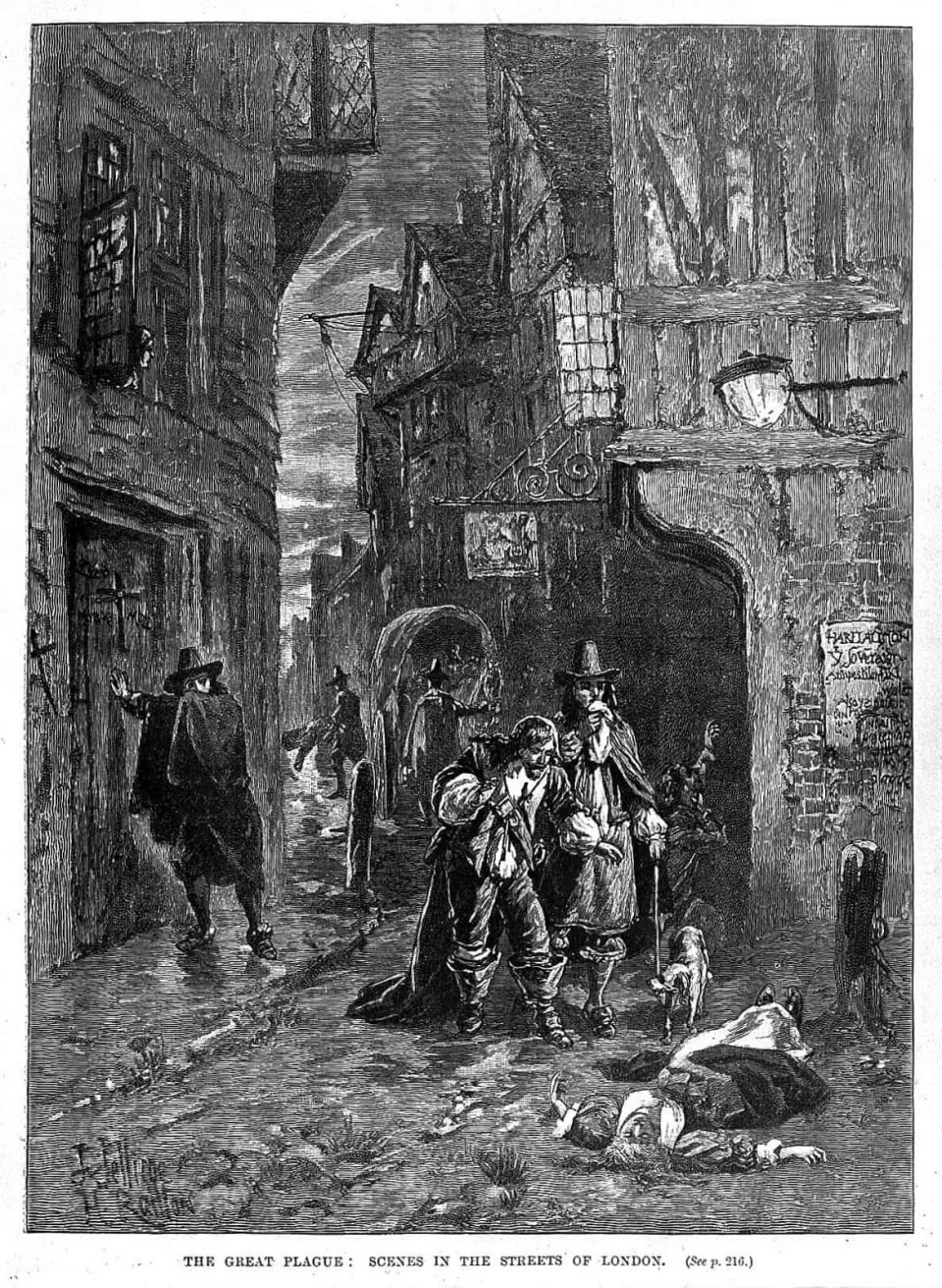

This image shows a bleak streetscape of London in 1665 recorded by the diarist Samuel Pepys, who provided an inestimable testimony of the Great Plague in London. On the left side, the cloaked man’s gesture indicates his disgust at seeing the body lying on the desolate street. The image vividly lays bare the horrors of the epidemic suffered by those living in poverty and simultaneously reveals the ignorance and callousness of the upper class via the portrayal of their detestable attitudes and behaviour.

3. Plague as an Enlightenment

Artists are inspired by the dilemma of human survival during the hard times, thereby presenting the traumatic experiences in their artworks as a reflection of the grim reality. From Sophocles’ account of the plague in Oedipus Rex to Boccaccio’s Decameron, Mary Shelley’s The Last Man to Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death, and Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice to García Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera, countless examples can be found of fictional realities in which the plague is wreaking havoc. The language of the plague can be viewed as social enlightenment, reminding people to consider what can be learnt from the plague across multiple generations. From the 20th-century French writer Camus’s perspective in his novel The Plague: “All a man could win in the conflict between plague and life was knowledge and memories.” (Part V)

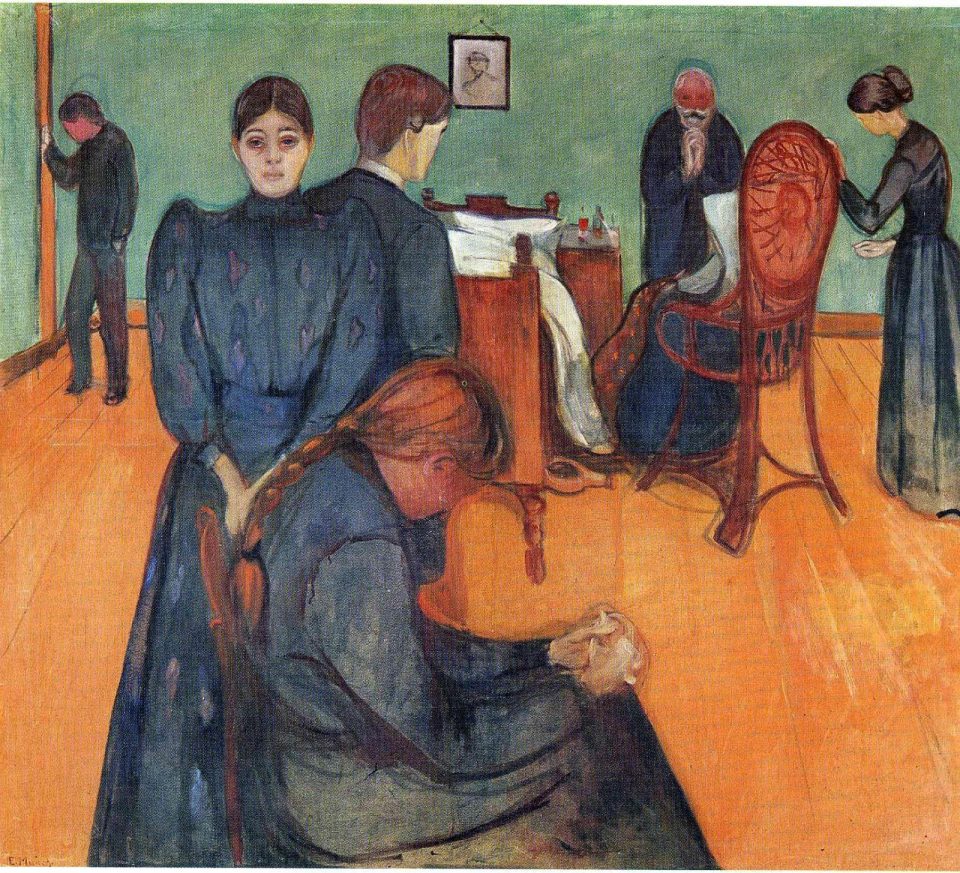

Credit: The Munch Museum

As Camus says, the plague made people newly aware of the pricelessness of family affection. In the painting above, the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch condenses the lifelong melancholia of losing his sister Sophie, who can be seen in the background sitting in a wicker chair. Munch’s family experienced the ravages of tuberculosis at the fin de siècle, and this sombre scene illustrates the way in which every family member’s sadness permeates the atmosphere in the room. Munch expressed his despair by materialising his memory into an aesthetic piece of art. At the same time, his expressive artworks effectively cultivate a historical insight into human existence that has aroused more consideration on plague as a contemporary issue.

Humanity is currently stricken by a worldwide catastrophic plague, the coronavirus pandemic. During the increased isolation forced upon us by the virus, more attention has been paid to historical accounts in various literary texts and artworks of previous infectious diseases. In Victor Hugo’s last novel Quatre-vingt-treize, he described the plague as a storm: “because it is a storm. A storm always knows what it is doing… Civilisation was in the grip of plague; this gale comes to the rescue.”

When things begin to fall apart on virus-plagued Earth, rescuing the lost ‘civilisation’ of humanity feels more important than ever, to bravely and firmly face the unknown ‘storm’ into the future.