Capodimonte National Museum is one of the largest museums in Italy, meaning you could spend hours if not days observing each and every artwork it houses. Located on the Capodimonte hill overlooking the city of Naples, it was previously the Bourbon family’s royal palace. It contains an ensemble of different collections, the most important of which are the Farnese and Neapolitan galleries, comprehending paintings by local artists from 1200 to 1700. The museum was established in 1757 following Charles of Bourbon’s need to find a place to store the collection inherited by his mother Elisabeth Farnese. Over the years, the palace was enlarged and filled with more art until a gallery housing the contemporary section was added in 1996.

Some of the most well-known pieces include Caravaggio’s Flagellation (1607–1608), Botticelli’s Madonna and Child and Two Angels (1470), Masaccio’s Crucifixion (1426), Titian’s Mary Magdalene (1550) and Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith and her Maid Servant (1645-50). If you happen to be in Naples and you decide to go to the Capodimonte Museum, these are the artworks that are labelled as the most crucial to see, but what is special about a museum is that it can be a place of wonder, a place where you want to be surprised by what strikes your attention during your visit. This is the reason why I have created a selection of four underrated highlights, artworks which you would probably not even notice if you spend your time in this museum walking directly to the most famous artworks.

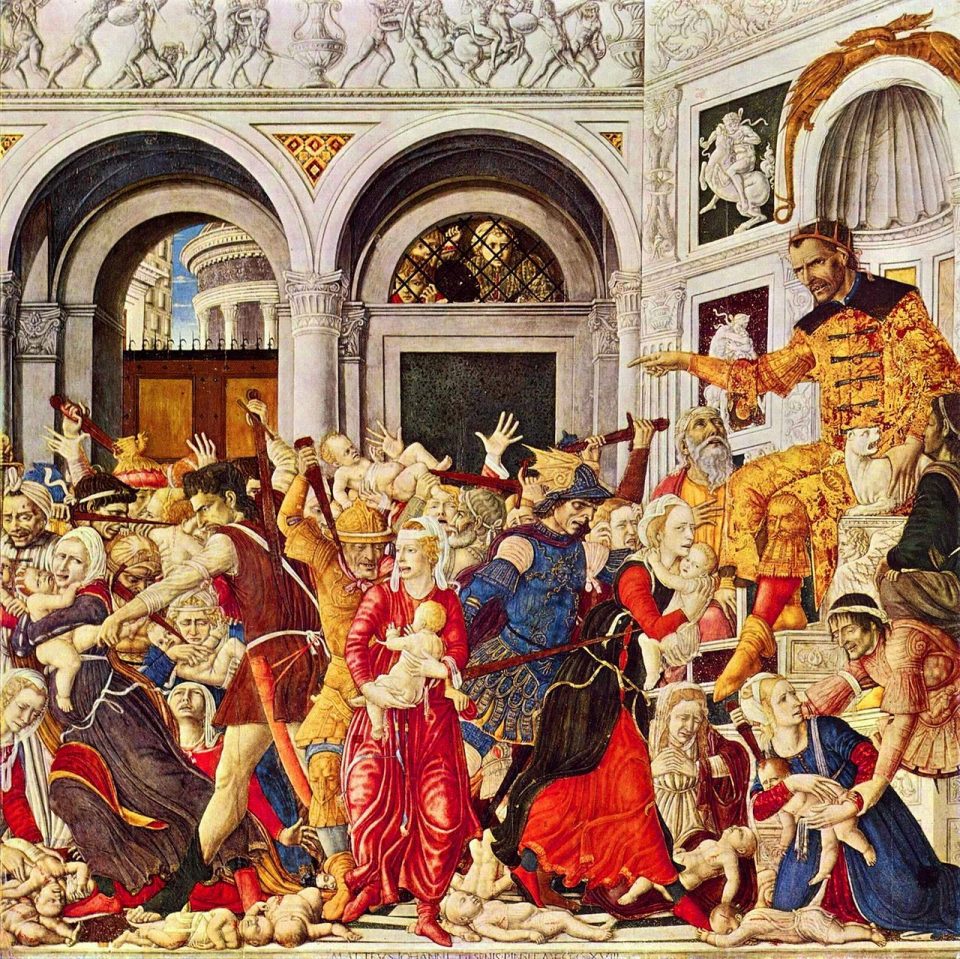

Our first stop is Massacre of the Innocents, a tempera on panel painting by Matteo di Giovanni executed between 1481 and 1488 in the Tuscan city of Siena and commissioned by Alfonso II of Naples. The scene represented by di Giovanni is the tragic moment in which the Ottomans enter the church of Santa Caterina at Formiello (Naples) and start killing everyone who is inside, predominantly innocent women and their children, generating a massacre. Interestingly, the church is represented with great detail, including the Ionic capital sustaining rib vaults and the reliefs above them depicting battle scenes from antiquity. What caught my attention is the facial expressions. Matteo di Giovanni – looking forward towards the Renaissance but still heavily influenced by the Gothic style – portrays women in a moment of profound suffering, expressing their emotions by screaming, crying or terrifyingly scrutinizing the invaders while the dead bodies of their children are lying on the church ground. It almost feels like the painting emits sounds due to the intensity of the image in its entirety. This effect is derived from the fact that the artist chooses to place the women and the Ottomans on the foreground at the expense of linear perspective – a feature that will later be key to the Renaissance style. This results in a way as if the characters are coming out of the space towards us but at the same time there is no perception of space between the figures, appearing like a vibrant conglomeration of bodies. The cropped figures on the sides suggest the existence of a larger image of which di Giovanni wants us to focus exclusively on this section. It resembles neither an idealized Renaissance scene of suffering nor a theatrical Baroque act; the artist wanted to highlight how pain distorts faces in different and unidealized ways. Lastly, the rich garments of the Ottoman leader sitting on the marble throne on the right – thus disproportioned confronted to the other figures below him – are depicted with such detail that is possible to spot the golden ornaments on it, including the depiction of a human head on his left knee.

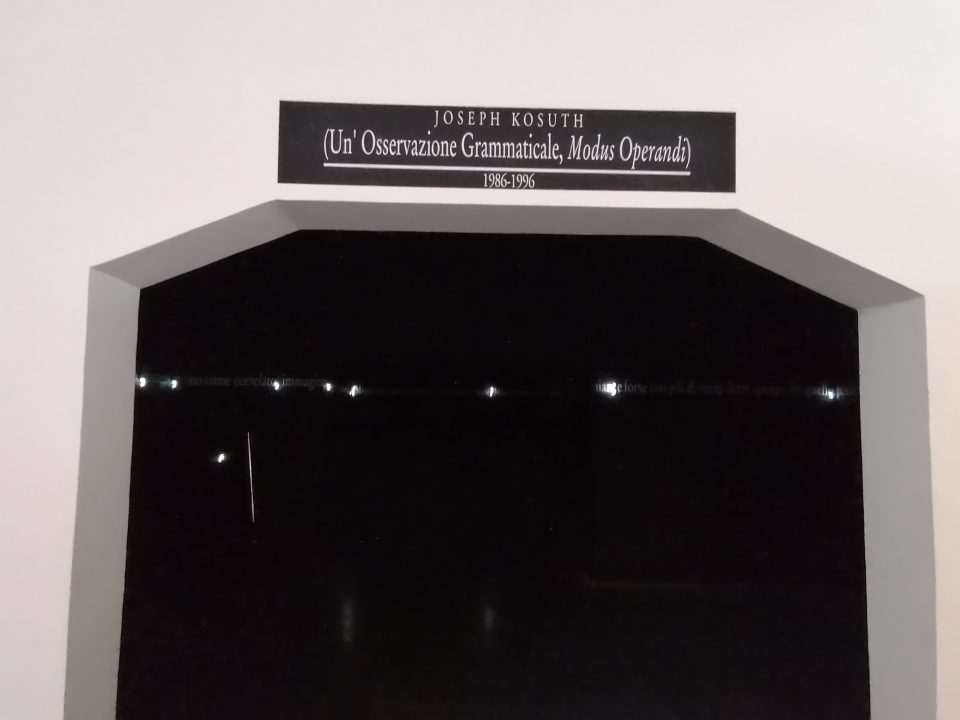

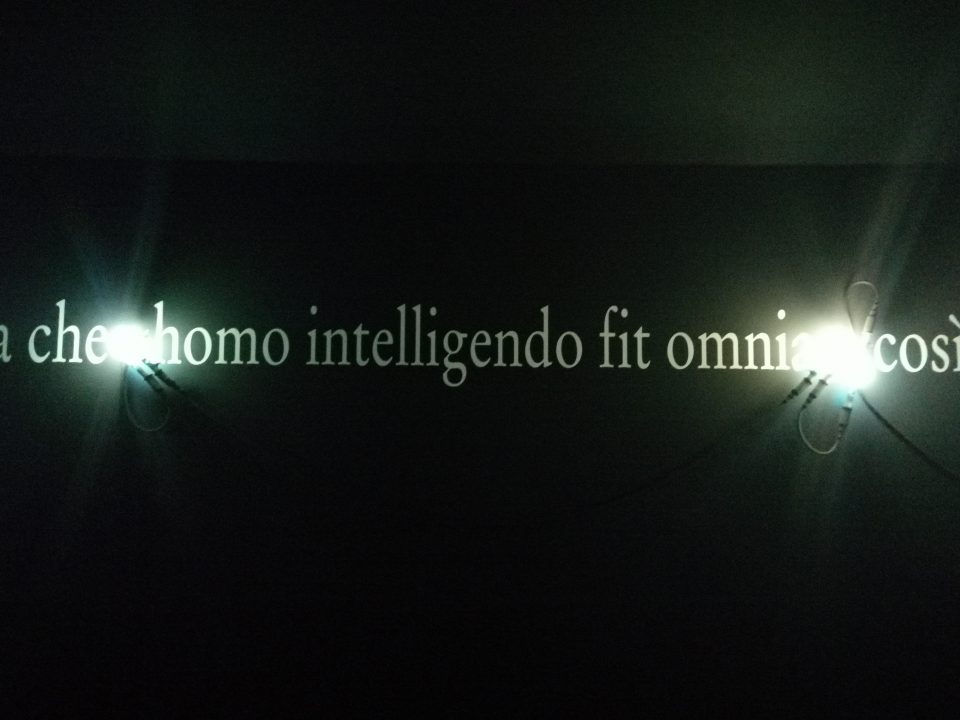

Our second stop is A Grammatical Remark. Modus Operandi by the American conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth. He is best known for combining art, philosophy and language resulting in a research focusing on the relation between the object and its definition. You have probably heard him before thanks to his famous piece One and Three Chairs (1965), an installation in which he presents a chair, the picture of the same chair and the vocabulary definition of a chair, thus questioning which one is the real object associated with the word. A Grammatical Remark. Modus Operandi is a 1980s installation in which the artist writes two quotes from the philosophers Gian Battista Vico and Ludwig Wittgenstein in white on black walls, a reference to the definition of art as an intellectual reflection and how it is able to shape our thoughts. What caught my attention while entering this dark room was the position of neon lights, used by Kosuth to determine the punctuation of the two quotes. In Vico’s quote, it is mentioned the Latin phrase “homo non intelligendo, fit omnia” meaning that our ignorance is the basis of our freedom. Change can take place only when we admit our ignorance because by admitting it we also demonstrate that we acknowledge our mistakes and are open to learning more. There are also two mirrors placed in two strategic corners of the darkroom, facing the observer while he is reading. One mirror is placed under the section of the quote that says “language appears related to the image”, pushing the observers to look in the mirror and stimulating them to think about the reflection – meaning in this case both the return of the image and the deep thinking that these philosophical quotes induce.

Credit: Belen De Bacco

Credit: Belen De Bacco

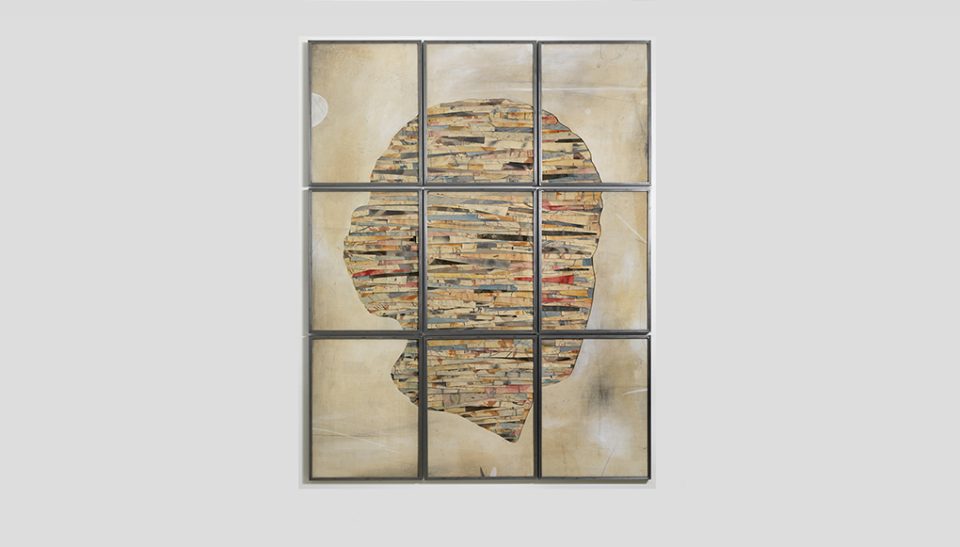

Our third stop is the polyptych Untitled by the contemporary Italian artist Umberto Manzo. This piece was completed in 2016 and it is made of a mixture of different techniques on paper, canvas, wood, iron and glass. Umberto Manzo studied art at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Naples. From the 1980s he started appearing on the national art scene, greatly developing his personal artistic language. He was one of the artists called to participate in the region’s project Stations of Art in which well-known contemporary artists were appointed to design new environments for some of the Naples metro stations as part of the city’s redevelopment project. Manzo’s most recent pieces focus on what he calls “archive-works”; the artist creates drawings which are placed overlapped in new frames, resulting in multi-shaped cuts whose silhouettes suggest the borders of classical statuary. What I particularly liked about this artwork is the way Manzo expresses his relation with Naples, the city where he was born and where he found his artistic voice. Inside the head of Aphrodite, goddess of beauty and passion, Manzo decides to place multi-shaped cuts which remind us of the history of Naples as a stratified city where Greek foundations coexist with street art, creating a multiple but simultaneously unitary narrative. Untitled represents an interesting combination of the fragility of classical statuary and its tension towards immortality, while also referring to the archive as perishable. It is important to notice that Manzo’s concept of archive is far from being a conservation container where the information is logically classified, he rather interprets it as the key to access memory and identity. The artist substitutes the stockpile of information with the irregular layering of memory, an act of revolution towards the perishability of the substance that involves both humans and objects. Hence, his artworks become both the expression of creativity and the document of history.

Our fourth and last stop is Translated Vase Special Edition of Napoli by the South Korean artist Yeesookyuong. It is a piece created in 2019 especially for the Whisper Only to You exhibition (2019-2020). It is interesting to observe that this artwork is made by 18th Century porcelain shards which derive directly from the Royal Capodimonte Porcelain Factory (established in 1743), which was a key production centre in the Spanish viceroyalty. In 18th-Century Europe it was impossible to be seen as a powerful and influential reign if the manufacturing sector was not developed. Porcelain was also called “white gold” and European manufacturers looked at China to better understand this new material. European courts used porcelain objects as gifts for important figures, thus showing off their richness and finesse. Porcelain was therefore considered as an object which detained political status and technical prowess. Unfortunately, Charles III ordered to establish a new porcelain factory in Madrid and destroyed the one at Capodimonte, thus transferring all the production to Spain as well as the best craftsmen. Yeesookyuong revives the Capodimonte Factory by masterfully combining porcelain fragments with plaster, polystyrene, epoxy and 24k gold leaf added in the fractures of the composition to create a sculpture which evokes a reinterpretation of an 18th-Century tradition in a contemporary setting. The concept of an artwork generated from waste is particularly intriguing, reusing material in order to create something new but still connected to tradition, teaching us that history is never a continuous line but rather an accumulation of imperfection and fragility. Yeesookyuong’s Translated Vase series launched the artist in the international art scene, who is particularly acclaimed for her versatility in different mediums comprising painting, sculpture, video, performance and installations. Her way of uniting East and West in her sculptures is proved by her use of European porcelain and the Korean style during the Goryeo (918–1392) and Joseon (1392–1897) dynasties.

Credit: Belen De Bacco

Credit: Yang Ian

From 13th Century to Contemporary art, from Egyptian-style clocks to tapestries, the Capodimonte National Museum is rich in its variety of artworks, aiming to have simultaneously a national and international vision by including sections on Neapolitan and international artists, as the presence of Yeesookyuong’s artworks proofs. The Capodimonte Museum teaches us that visiting art museums has to become a way of educating how to look. The highlights of the museums and the most famous masterpieces are always pointed out by the museum maps but it is important to encourage to have a wider look at what is around you rather than just stopping at the artworks you know. It has to be reminded that the visitor is the one who has the power to decide which artworks to stop by and how much time to spend experiencing them. We are all different people with different tastes and we also react in different ways to artworks, both intellectually and emotionally. The museum experience is highly subjective and depends upon what every single one of us puts into it. Museums are places for everyone, not just élite intellectuals or art history students. Everyone can enjoy a museum visit and learn from it. It is a cultural centre that reunites different thoughts and ways of expression.

The next temporary exhibition at the Capodimonte National Museum will be Gemito. From sculpture to drawing and will run from 10th September to 15th November 2020, comprising 19th-Century artworks of the Neapolitan artist Gemito. After the great success of this itinerant exhibition in Paris, it will finally arrive in the artist’s birth city.

http://www.museocapodimonte.beniculturali.it/portfolio_page/prossime_mostre/