The Pacific Northwest has always enchanted me. For those unfamiliar, this is the area—also known as Cascadia—of Canada and the United States that encompasses Oregon, Washington, and British Colombia (plus debatably parts of their surrounding neighbours). With its towering, almost fluorescent green trees and mountains running through the landscape like veins, it is a destination that feels singularly alive. I find myself coming back here again and again, each time coming away breathless for more. Strangely enough, however, I had never delved too deeply into the Cascadian art scene. Of course I had visited gardens, state parks, and little tourist trap galleries on the coastlines, which are artful enough in their own right, but never a specific art museum.

I recently have been back in the PNW to visit my brother in Portland, Oregon. This progressive, diverse city has an unofficial motto: “Keep Portland weird”. And weird it is, but in the best sense. Portland is overflowing with creativity. Around every corner you will find street art, micro-breweries with designs on the bottles as hypnotic as the drinks themselves, and friendly faces as open and eclectic as the city in which they reside.

Many cultural heritage institutions around the US have been closed due to lack of funding in the wake of COVID-19, but the Portland Art Museum is one of the lucky ones that has managed to reopen. It was founded in 1892, is the oldest museum in the Pacific Northwest, and the seventh oldest museum in the United States. It is especially distinguished for its collection of art of the First Nations peoples of North America. This was my first time visiting. The experience was exhilarating, especially after months of not being able to see any art in person. I found the collection to be original and striking in its content, and was able to find some real gems.

VOLCANO! Mount St. Helens in Art is the current exhibition on view at the museum, and commemorates the 40th anniversary of the Mount St. Helens volcanic eruption of 1980. It is a celebration of nature with its destructive and regenerative capacities, as well as artists’ profound ability to nurture creativity with destruction. The exhibition’s set-up poignantly delineates the overbearing sense of ‘before and after’ that St. Helens evokes. It is set up chronologically, beginning in the first room with gorgeous pre-contact Native American basalt and obsidian utilitarian objects, and ending with the most recent contemporary depictions of the volcano. Colour is used in this exhibition to denote the massive change that took place when St. Helens erupted—starting bright, but abruptly fading to grey. In the second room, paintings from as early as the mid-1840s provide a serene, pastoral depiction of the mountain. Mostly in lighter shades, the room feels bright, if a little boring. Though the artists’ unique styles are evident, the paintings are too optimistic, too plain. Pretty landscapes they may seem, but these works, for me, are tainted with Manifest Destiny and Romanticism. They scream, “Look at this beautiful mountain! And these beautiful trees! And rivers!”. I want to scream back, “That you stole!”…but I digress.

The next room is my favourite. It explodes with colour. And this is no coincidence, as these are the artworks that depict the actual explosion on May 18th, 1980. The artworks are beautiful and terrible, as bright and complex as the eruption. One piece in particular was my favourite of the exhibition: Mary Davis’ The Mountain Speaks— Softly. This dreamy painting captures the mountain’s mystic qualities, with visible brushwork that feels ashy, foggy, as if the entity within is literally speaking through its smoke. The deep blues and warm hues offset one another, a dichotomy that speaks to the violence and renewal of the blast. In the right hand corner, eyes glow through the ash—one cool toned, one warm toned. Through these glowing orbs, the duality of the spirit of St. Helens is meditated upon. There is not simply catastrophe here, but also rebirth and renewal.

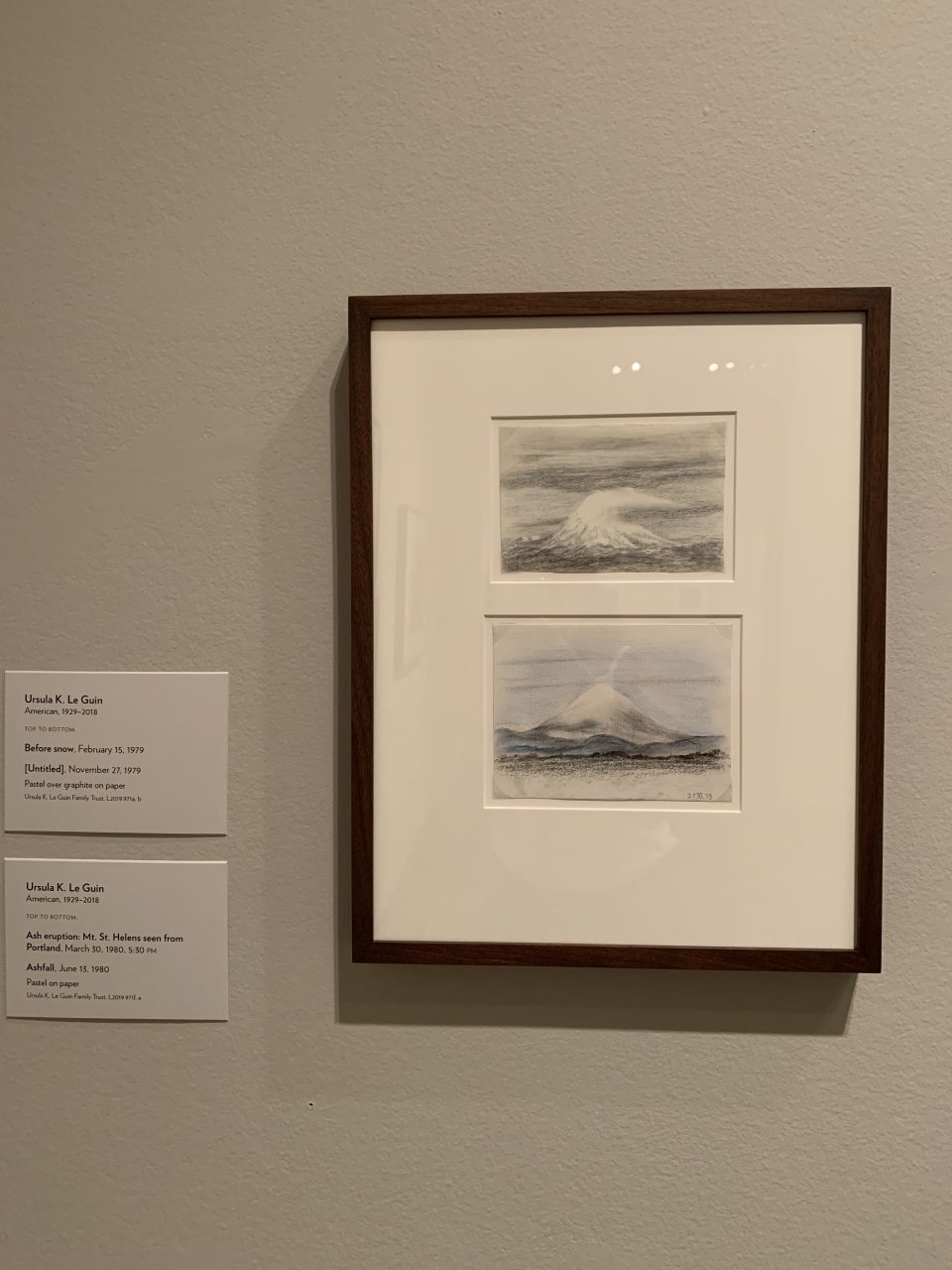

The last few rooms are the ‘after’. Nearly every artwork in these rooms is in a shade of grey. Photographs of trees blown to the ground, ash falling from the sky, a lake upheaved from its previous location…it is sobering. The beauty of the blast thought possible in the previous room seems a sick joke when the desolate feeling in these pieces permeates the room. A favourite science fiction writer of mine, Ursula K. Le Guin, lived in Portland and documented both the pre and post-eruption volcano using pastels. Her artworks are arresting; St. Helens looks as if it belongs to an otherworld. It is easy to imagine that Le Guin was inspired by this barren landscape in her writing. She is quoted, “…the fear I felt that day went deeper than the physical. After driving miles up through the endless green vitality of a great forest, to turn a corner and enter a world of grey ash, burnt stumps, and silence—from the complexity of flourishing life into the awful simplicity of death: the fear I felt was metaphysical.”

Ursula K. Le Guin (American, 1929–2018). [Untitled], November 27, 1979. Pastel over graphite on paper. Ursula K. Le Guin Family Trust.

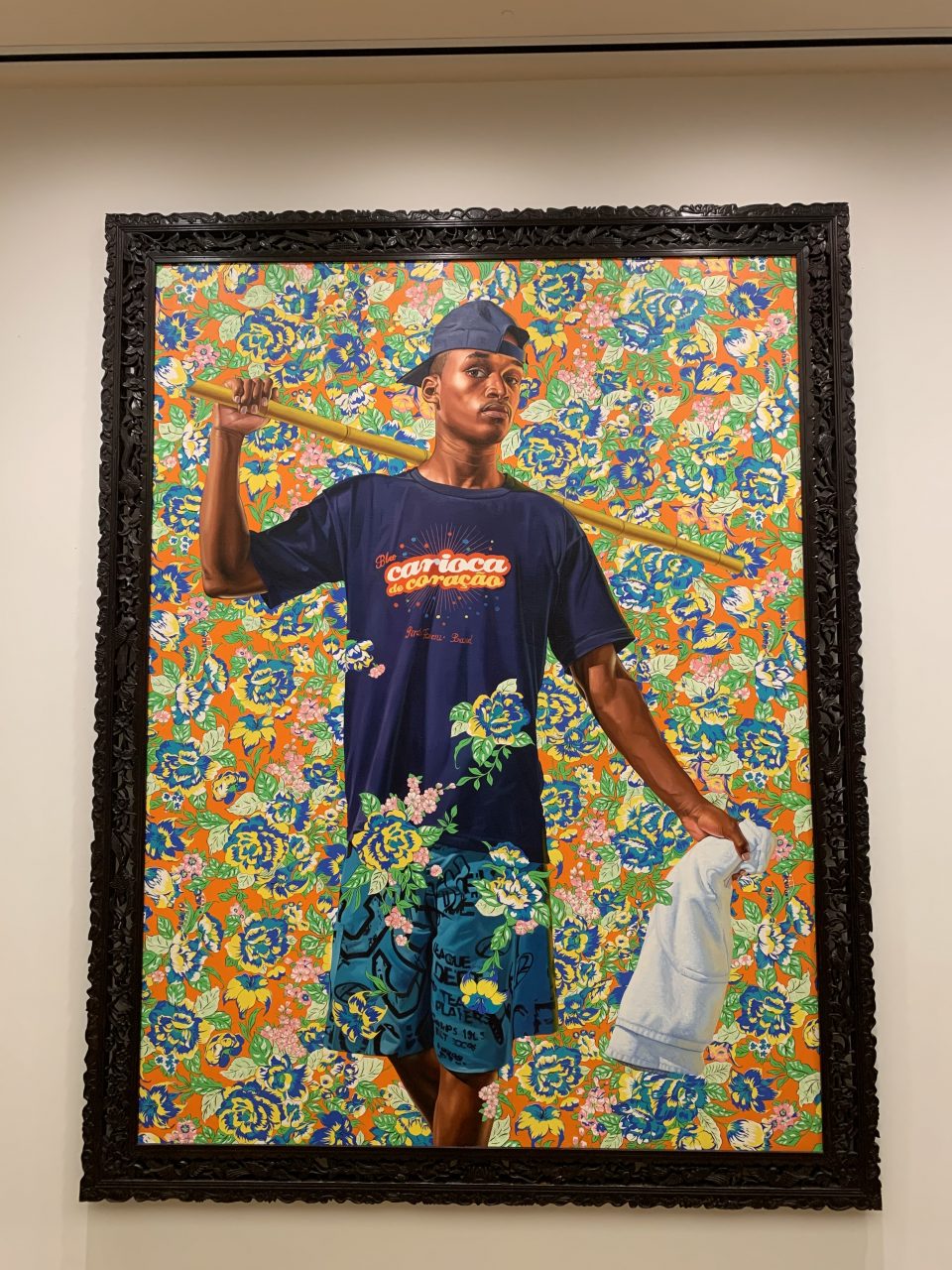

Moving along from the St. Helens exhibition, I didn’t have much time to spare, as museum slots were limited to an hour, and my slot was booked for the hour just before closing. I wandered aimlessly for the twenty minutes that I had left (although I do wish I had been a bit more proactive—I missed so much!). In a wide hallway on the bottom floor basement, was a portrait by artist Kehinde Wiley. I may have let loose a squeal; I had been wanting to see one of his artworks in person for almost three years, since it was announced that Wiley would be painting Barack Obama’s portrait. Indio Cuauhtémoc (The World Stage: Brazil) depicts an Afro-Brazilian man in a heroic stance. His clothing is casual, but his pose and facial expression exude power, unapologetically grandiose and regal. However, this is more than a celebration of the African diaspora; it is a harsh critique of colonialism. The tropical print backdrop that surrounds him condemns the fetishisation of the ‘tropical’, something Americans are very guilty of in their clothing and holiday tastes. Cuauhtémoc was the last emperor of Tenochtitlán, and this painting echoes the stance of his statue, which resides in Rio de Janeiro. The emperor was executed by the Spanish, a nod by Wiley to the not-so-distant past colonialism that still pervades world cultures.

The next room I found, just up the stairs from the basement, was filled with European and American art from the turn of the 20th century. Among the Rodin sculptures and Monets, I found an artist that I had never heard of before. Childe Hassam’s mesmeric Nude in Sunlit Wood shows a side of Impressionism not often seen, with its absence of overbearing contrast in colouring. A woman stands nude in a forest, gazing through the trees. The trees move in the sunlight, almost glittering in the breeze, but the woman’s stature is neutral, shaded by the canopy above. Indeed she could pass for a statue, with the trees billowing around her figure as she stands perfectly still. The limited colour palette creates a natural ambience— of greenery, of golden light and flesh, and undulating leaves.

The last room I visited (before I was nudged to leave at closing) was filled with Abstraction. Hilla Rebay is best known for her career as an artist, but also as the co-founder and first director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Her work Orange Accents was my favourite artwork in the Portland Art Museum. I will mostly let it speak for itself, but for me, it was a spiritual experience gazing at this painting. This is not surprising, as spirituality was both interwoven and integral to Rebay’s art. Her vision was for viewers to be able to commune with the art in a ‘museum-temple’—hence the co-founding of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Like the Pacific Northwest, her Orange Accents feels alive. Geometric lines like anchors grasp onto the movement beneath them, struggling to hold onto Spirit itself, ever-changing and evolving.

The Portland Art Museum is a hidden gem, just like Portland itself. If you ever get the chance to visit the city, I would highly recommend going to the museum. For now, on their website you can find online exhibitions and myriad other features, such as virtual reality film festivals, linked here: https://portlandartmuseum.org/