“Beauty, science and art will always triumph”. These words contained in a letter from 1958 well synthesise the message and future hope that the works of Christo leave to us. To celebrate one of the most important representatives of large-scale installation art, it will be attempted to uncover the (symbolical and political) significance of his work.

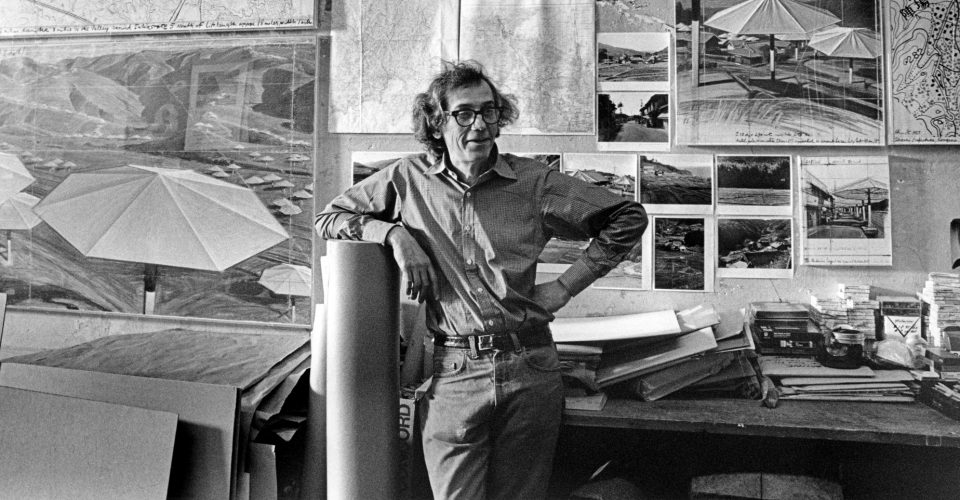

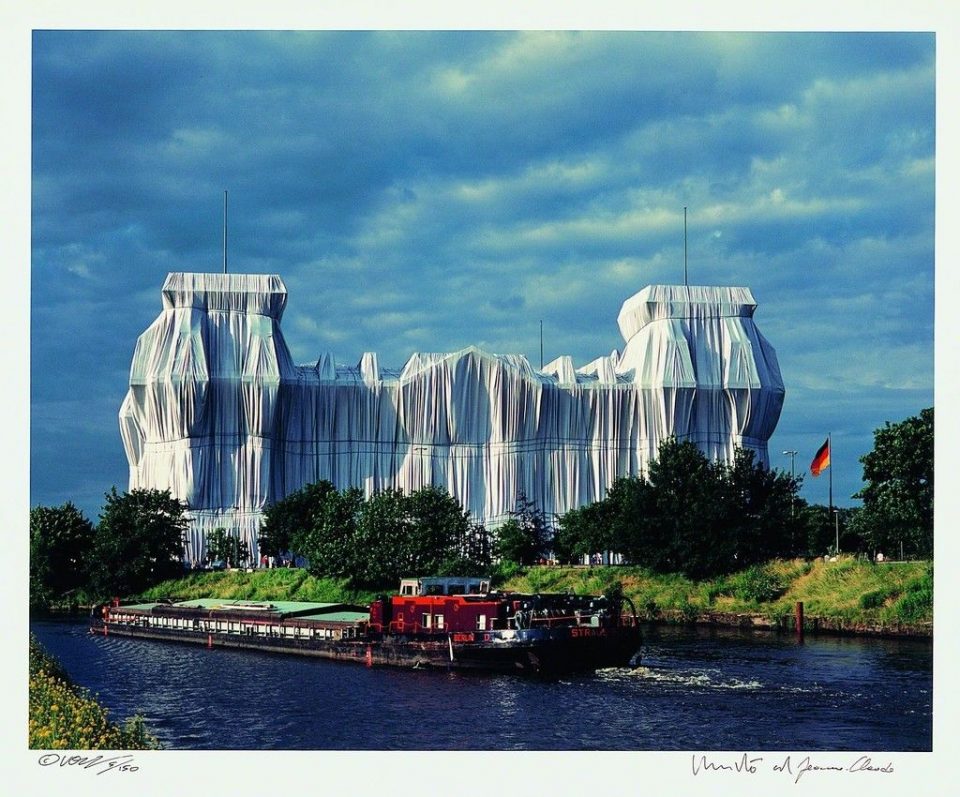

Born in Bulgaria and studying between Prague, Vienna and Genève, Christo Vladimirov Javacheff begins his artistic career in Paris in 1958, living at the margins of society and making a living working as a portraitist. It is precisely in Paris that he meets his life-long partner Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon, forming a romantic and artistic bond that will last until her passing in 2009. Working together to their artistic projects under the name of Christo and Jeanne Claude, the couple creates art that transcends the traditional limits of painting, sculpture and architecture. Most importantly, their art is inherently free: a fundamental condition for them is the ability to financially support their projects without accepting any sponsors. This is an overt aesthetic decision, which allows the art to be free of any influences and to transmit a message of love and beauty which is detached from the business logic of profit. Freedom also acquires a political connotation since the very beginning of Christo’s career, when he escaped from the Communist-ruled Bulgaria to realise his artistic ambitions freed of any influences. Politics plays a fundamental role in the choice of the sites for the environmental art (both urban and rural) that Christo and Jeanne-Claude create. Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin 1971–95 emblematically encapsulates this concept. Conceived during the Cold War but only accepted post-Reunification thirteen years later, the project employs the political sensitivity of the chosen site to symbolically hide the past history behind a Classical drape and create a blank slate for democracy and modern German identity, whilst also pondering on the impermanence and transience of life (and art).

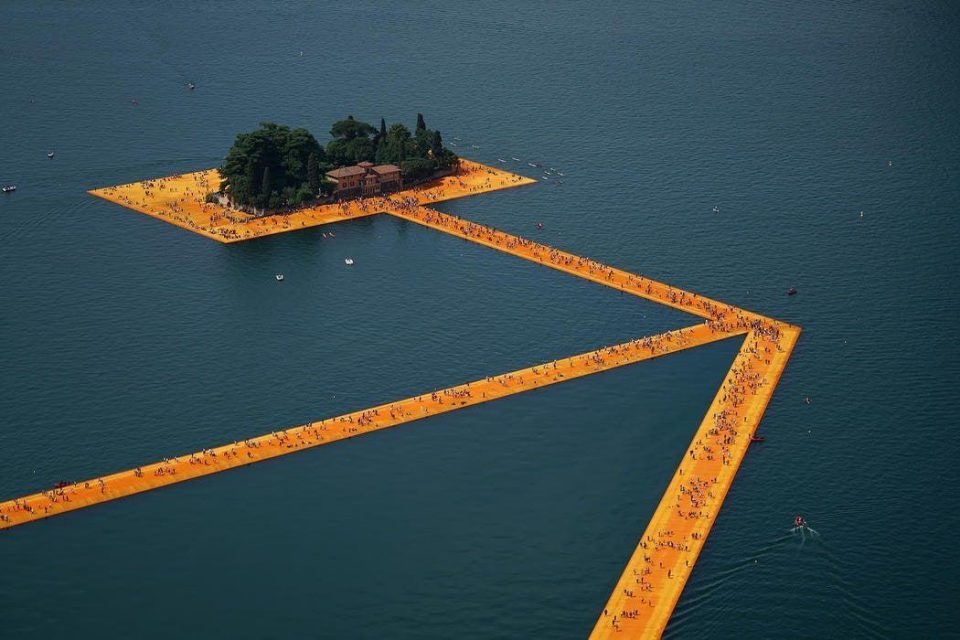

The poetics of Christo and Jeanne-Claude consists in transforming the world into a canvas which supports its representation, adding a “quality of love and tenderness” to their work as a further aesthetic quality. The ephemeral, temporary yet shocking nature of their installations challenges the established belief in the immortality of art, but also creates an even greater urge in the viewers to see and experience the artworks. With simple, fragile materials such as fabrics, ropes and cloth, the artists are able to radically transform a landscape and the knowledge and familiarity that its inhabitants have accumulated over time. One of Christo’s most recent public artworks, Floating Piers (2016), involved the reimagining of Lake Iseo in Northern Italy through the construction of a temporary floating dock system, rising just above the water surface and covered in shimmering yellow fabric. During sixteen days, more than a million visitors could freely experience “walking on water” from Sulzano to the islands of Monte Isola and San Paolo, with the installation functioning as a striking extension of public soil, just like a city street. The entire realisation process of this artwork, from planning to the construction of the piers, was documented and the footage from two years’ work became the film Christo – Walking on Water, an ode to land art which provides insight into the complexities of creating large-scale public artworks.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude never provided explanations of their work and its subtle implications – “we make beautiful things, unbelievably useless, totally unnecessary”, Christo recently declared. However, it is interesting to analyse the totality of their projects, as it reveals an attempt to reshape people’s relationship to the landscape and to illuminate under a different light the spaces citizens experience daily by opening up new perceptive possibilities. Through his art, Christo has given new significance to the imaginative and symbolical potential of the (extra)ordinary land we inhabit.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin 1971–95

Jeanne-Claude and Christo on the roof of the Reichstag during the realization of “Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin 1971-95” (June 1995)

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Floating Piers (2016)

Christo at the installation Floating Piers (2016)

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Floating Piers (2016)