Dr Willliam Hunter was not only a famous Scottish anatomist but also an avid art collector. Within The Hunterian Art Gallery collection, the artworks by the Scottish Colourists instantly catch a visitor’s attention due to their bold colours and lively brushstrokes. F.C.B. Cadell, John Duncan Fergusson, Leslie Hunter and Samuel John Peploe are the main figures of this artistic group, which was not as unified as the avant-garde movements that were emerging in the early 20th century in Paris. They never published a manifesto stating a common vision or the aim of their artworks but they did have a similar artistic development. At some point in their lives, each Scottish Colourist artist had been to Paris and their style was influenced by the French avant-garde art movements, mainly but not limited to Cubism and Fauvism. These artists offered a fresh perspective that strongly contrasted Realism, the dominant style in Scotland at that time. The UK art market started being interested in Scottish Colourist artworks around the 1920s, catching the Scottish collectors’ attention and convincing them to buy these artworks. By the beginning of the 1900, Scottish Colourists’ works could be seen on display in galleries in Edinburgh and Glasgow.

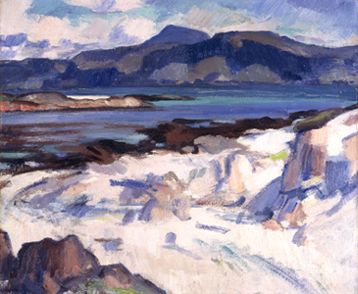

Ben More from Iona (1920-1930) – Samuel John Peploe, GLAHA:43995

One of my personal favourites is Samuel John Peploe’s oil on canvas titled Ben More from Iona, produced between 1920 and 1930. Peploe decided to paint Ben More, meaning ‘the great mountain’ in Gaelic, from the point of view of the island of Iona, which is located on the Western coast of Scotland. He came here with his friend Francis Cadell for the first time in 1920 and from that moment the two artists started to regularly work together on the island, creating landscape paintings that will be crucial to the evolution of the Scottish modernist style. This particular view of Ben More from Iona was explored multiple times by Peploe from different vantage points, a characteristic that was typical of Impressionist paintings. He focused on the vibrant colour combinations as it can be noticed from the blue tonality, key to the study of light and its reflection on the water. Peploe’s work captures more than simply a landscape scene, it is capturing an atmosphere, a temporary view which will change according to the weather and the time of the day. Therefore, each painting represents a slightly different impression of the same view. People had visited France where he closely observed Cezanne’s geometric style, adopting it in the form of landscape painting. This can be seen from the prevalence of geometric shapes in the overall composition, imposing a clear-cut distinction between different areas of colour.

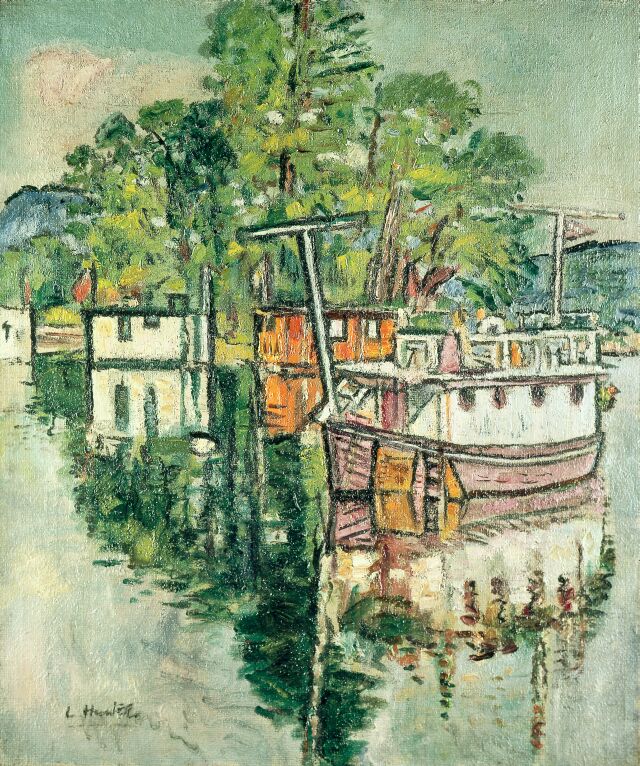

House Boats at Balloch (1920-1931) – George Leslie Hunter, GLAHA:43902

Moving on to our second highlight, you may notice George Leslie Hunter’s boats at Balloch. Hunter was born in 1877 on the Isle of Bute, in Scotland and he emigrated with his family to California in 1892. He was offered to exhibit his works at a gallery in San Francisco in 1906 but the city was tragically hit by an earthquake the night before the exhibition was supposed to have opened, therefore the gallery and all of Hunter’s works in it were destroyed. He then moved to Glasgow soon afterwards where he started developing his own style alongside Cadell, Fergusson and Peploe. What is interesting to point out is that Hunter had no formal art training, he was largely self-taught. His paintings are critically acclaimed for their treatment of light. In fact, Alexander Reid, a contemporary critic, noted of the artist that his still life paintings ‘show a mastery of form and colour that takes one back to the triumphs of the Dutchmen.’ In 1924, Hunter rented a houseboat at Balloch on Loch Lomond (near Glasgow) where he painted the oil on canvas titled House Boats at Balloch. Instead of choosing to depict landscape paintings of the south of France, as it was common at the end of the 19th Century, Hunter prefered to focus on the local Scottish landscape. This leads us to understand that Scottish Colourists artists wanted to imitate the French avant-garde style but at the same time, they wanted to change the subject, including Scottish landscapes in their works. In this painting, Hunter explores the interrelationship of landscape and water, drawing on the Impressionist ‘en plein air’ tradition (which means ‘in the open air’). This is a significant change in art history because for the first time, artists are no longer painting in their workshops and by memory but rather trying to capture a momentary scene, distancing themselves from the predetermined academic image and developing a greater sensibility towards light instead of details. The work pays homage to Claude Monet’s water lilies series, which Hunter had previously seen in a gallery in New York. The contrast between the geometrical house-boats and the rippling effect in the water alongside the orange tonality contrasting with the green, creates an overall sense of harmony and balance.

Tulips and Cups (1910-1914) – Samuel John Peploe, GLAHA:41370

Moving on to Samuel John Peploe, he studied at the Royal Scottish Academy school and then at the Académie Julian, a private art school in Paris where also Fergusson and Cadell received their training. Studying in France led People to become more involved in the Parisian modernist artistic circle. Fauvism was one of the avant-garde movements that strongly influenced Peploe’s style. The first Fauvist exhibition took place at the 1905 Salon d’Automne in Paris. This was a style characterised by the use of fierce brushstrokes alongside pure colours, as we can notice in Peploe’s oil on canvas titled Tulips and Cups, realised between 1910 and 1914. The depiction of reality and the use of naturalistic colours does not apply to fauvist-style canvases. The emphasis on colour results in the flattening of the composition, reducing the illusion of depth. In order to intensify its expressive power, Fauvist artists studied the scientific colour theories developed in the 19th century with particular attention to complementary colours. Complementary colours are pairs of colours which appear opposite to each other on the colour wheel. When these are used side-by-side in a painting — for example red and green, blue and orange in Peploe’s oil on canvas — the result is that each colour makes the other look brighter and more vivid thanks to the colour contrast. The painting is also characterised by a higher degree of simplification and abstraction of the subject. Fauvism represents the very first break from the Impressionist tradition; artists are no more interested in depicting impressions, instead, they want to show their individual reinterpretation as an expression of the artist himself, with the act of painting becoming instant and instinctive. It is interesting to observe that the rapidity and expressiveness of the thick and angular brushstrokes in Peploe’s still life are also loose and rhythmic. This paradoxical feeling evokes both movement and speed, stillness and monumentality.

Anne Estelle Rice in Paris (1905-1910) – J.D. Fergusson, GLAHA:43487

The last artwork I would like to highlight is by John Duncan Fergusson and marks the transition between Fergusson’s earlier style — closer to Whistler and the Glasgow Boys — to his more Fauvist and Post-Impressionist styles. Before the Second World War, Fergusson spent many years in France. It is here where he first met Anne Estelle Rice in 1904, an American artist and illustrator for a Philadelphia magazine. Miss Rice and Fergusson both became active collaborators for the literary, arts and critical review magazine called Rhythm, edited by John Middleton Murry and published in London from 1911 to 1913. Regarding visual art, Anne Estelle Rice took a similar path as Fergusson, adhering first to the Impressionist and later to the Fauvist movements. The portrait titled Anne Estelle Rice in Paris was completed by Fergusson in 1910. Reminiscent of the Impressionist tradition, the oil on board was executed ‘en plein air’ and specifically set in the fashionable neighbourhood of Montparnasse, with the café Closerie des Lilas in the background. The harsh brushstrokes, the vivid colours and the use of green to represent shadowed areas indicate Fergusson’s first experiment with Fauve portraiture. He supported Matisse’s idea of art as a means of ‘emotive expression’ in which colours are used to evoke the emotional and intellectual characteristics of a subject. One of the most interesting features of this painting is Miss Rice’s gaze towards the viewer. Normally, in portraits depicting women, the sitter avoids looking at the observer, leaving the power of the gaze to an implied male viewer. Miss Rice, on the other hand, defies this common practice and decides to regain that power by returning her gaze.

The Hunterian Art Gallery is the perfect getaway of these days. Immersing yourself in such a rich and varied collection, taking a break from the world outside while enjoying the peace and tranquillity that transmits the gallery is something I would highly recommend.

The Hunterian Museum and The Hunterian Art Gallery are now open. Admission is free.

Why not pre-book a tour of The Hunterian led by one of the student volunteers? Tours last 15 minutes and are limited to two tickets per tour. Each ticket admits up to a maximum of three people from one household. Pre-book your tickets here: https://www.gla.ac.uk/hunterian/visit/tickets/

Tours run at 11am, 1pm and 2pm Tuesday to Friday, 11am and 2pm on Saturdays and 12pm and 2pm on Sundays.

Tour tickets include general admission to The Hunterian. For more information visit The Hunterian website https://www.gla.ac.uk/hunterian/