I recently saw a mural being painted on the corner of a street near mine. It represents two black women, one sat on a chair and one standing up, wearing colourful clothes against an abstract backdrop. It’s beautiful: decorative with vibrant colours and illustrative (both literally and figuratively) of the diverse community in this North London neighbourhood. It reminded me of the large murals you can find everywhere in Glasgow, commissioned by the City Council and created by spray paint artist Rogue One (@rogueoner) – I suddenly missed that city very much. Local artworks such as these have a clear purpose: to brighten and rejuvenate streets, prevent urban decay, offer local attractions and even encourage tourism. After all, Glasgow city centre has so many murals that the Council has created a website dedicated to the “Mural Trail” (which, by the way, is an excellent way to spend a lockdown afternoon).[1]

Generally, the public agrees that street art should be democratic/anarchist, unregulated, free, subversive, even clandestine, and not-for-profit. That is a somewhat outdated image, however. Street art originated with the emergence of graffiti as an artistic form of expression of sub- and youth cultures in the United States in the 1970 and ‘80s.[2] But towards the end of the 20th century street art had evolved into a multidisciplinary art form, firmly established in contemporary art. It was no longer necessarily clandestine, illegal, or subversive, and as we have seen, today artists are frequently being commissioned to help regenerate urban environments – as opposed to playing a part in their degeneration. The commercialisation of street art was inevitable, especially given the boom of the art market in the 1980s, and parallelly, the degree to which this has happened came under discussion. Street art by its very nature is public and belongs to everyone. If artists sell copies of their work, is it still street art? If they remove originals off the street is it still street art? It is obvious that if artists didn’t do this, they wouldn’t make a living. But when fame, art market value, and the interests of agents, auction houses, museums and galleries are added to the balance, the question becomes more complicated. This article looks specifically at Banksy in an attempt to discuss some of the major points of contention with regards to his oeuvre (and notoriety), but there are other examples of street artists who have become famous and whose artistic practice was changed as a result.

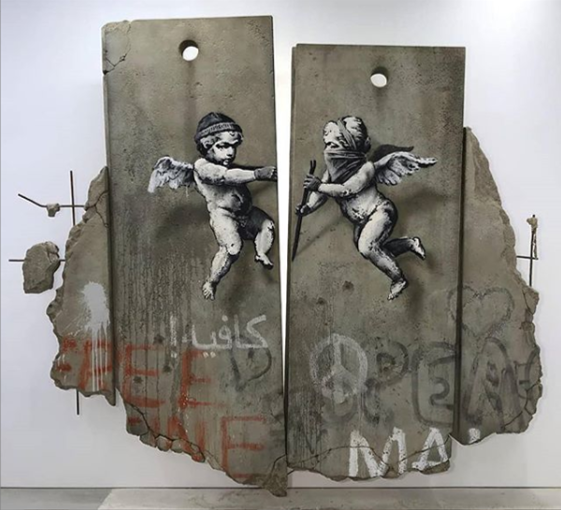

Banksy, a UK-based artist who has been active since the 1990s, became internationally famous because of his witty/satirical, politically engaged tags, distinctive black-and-white stencilling, and the fact that he has successfully remained anonymous. Best known for street art (specifically graffiti), he has also engaged in performance art, mounted exhibitions, created a documentary and even a large-scale installation called Dismaland, which parodied theme-parks and consumerism. Banksy originally maintained a kind of guerrilla-artist image, though he sold more and less expensive stencils and prints through the platform Pictures On Walls (POW). Over the years, however, his work became so popular and recognisable that the art market started to take advantage, in the way the art market does best: by reselling (from which an artist does not receive a cut in the US, or only 4% in Europe) as opposed to selling (from which the artist does make direct profit). Notably, and controversially, many of his public works have been stripped off the walls they were spray painted on, first auctioned off, then resold at even greater prices. A process which is legal, though it seems wrong, and represents everything Banksy claims to stand against.

Of course, the art world has a history of embracing those who criticised it, institutionalising institutional critique. Banksy, however, appeared at least to resist this process by practically halting the sale of his prints or selling works at prices far below market value from around 2010 onwards.[3] In October of 2018 Banksy made headlines for the prank he pulled at Sotheby’s where his painting Balloon Girl shredded itself through a mechanism built into its specially-fitted frame at the exact moment it was auctioned off. Sotheby’s quickly claimed they had no previous knowledge that this would happen, but added that the work, now retitled Love is in the Bin, was “the first artwork in history to have been created live during an auction.”[4] Naturally, the value of the painting increased and the buyer decided to go through with the purchase. Publicity stunt or genuine dig at art-market inflation? Due to the secretive nature of the art market, it remains unclear whether the artist financially profited from this stunt. Certainly, he became more famous and more controversial than ever before.

Banksy art and knock-offs have become as commercialised as Van Gogh’s Sunflowers. Merchandise with prints of his most famous stencils, such as the Balloon Girl, is available everywhere. If anything, it is more profitable than merch with some of the world’s most famous fine art BECAUSE Banksy’s work is street – popular, or low – art. Like concert or band t-shirts, Banksy merch projects a certain ‘90s, street-cool, stick-it-to-the-man attitude. But like concert t-shirts, which are currently available in most high-street shops and no longer need to be purchased at the source (that is, concerts), Banksy art has become the mainstream of street art. Perhaps that is why it is so divisive as street art; by being commercialised to the point of becoming mainstream, whether this happened against the wishes of the artist or not, it fundamentally undermines what street art started out as. It now really belongs to everyone, but stopped meaning anything. It has become a part of the thing it protested (i.e. the endless cycle of trends, production, and profit margins) and lost its power.

[1] For more information, see https://www.citycentremuraltrail.co.uk/

[2] Bojan Maric, “The History of Street Art,” Widewalls.ch, 29 July 2014. https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/the-history-of-street-art

[3] Loney Abrams, “How Does Banksy Make Money? (Or, A Quick Lesson in Art-Market Economics),” Artspace.com, 30 March 2018. https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/close_look/how-does-banksy-make-money-or-a-lesson-in-art-market-economics-55352

[4] Eileen Kinsella, “Banksy Authenticates and Renames His Shredded $1.4 Million Painting—Which the Buyer Plans to Keep,” Artnet.com, 11 October 2018. https://news.artnet.com/market/banksy-re-authenticates-shredded-1-4-million-european-buyer-will-keep-1369852