Continuing with the Peggy Guggenheim Collection theme, today I want to present to you one of the rare female figures displayed in the permanent collection, whose work Tauromachie (1953) is at the entrance of the garden. Although Germaine Richier was known as one of the most avant-garde artists in her time, I see from my own experience as an intern at the Collection, that tourists do not pay as much attention to her as to Giacometti’s two nearby sculptures – “This is a Giacometti, see I was right! And this instead? Richier? I do not know this one”. And it is this lack of concern, probably not deliberate, that made me want to dive into her artworld.

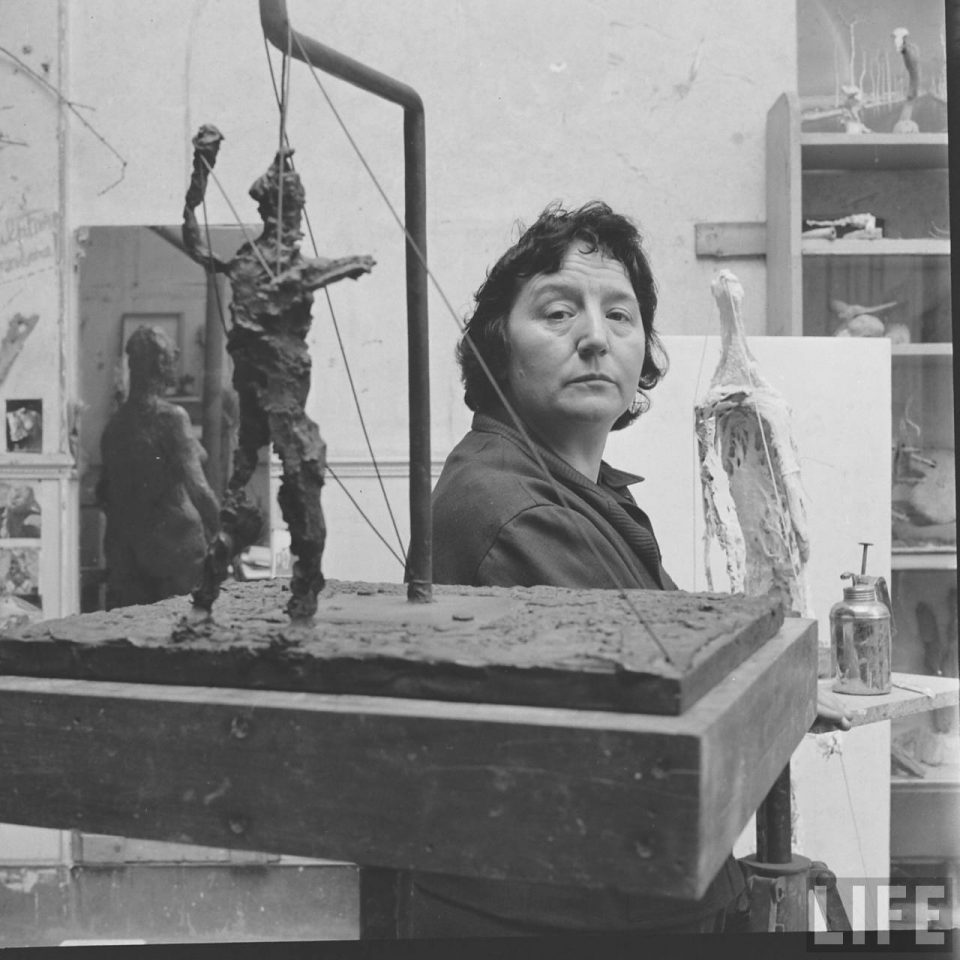

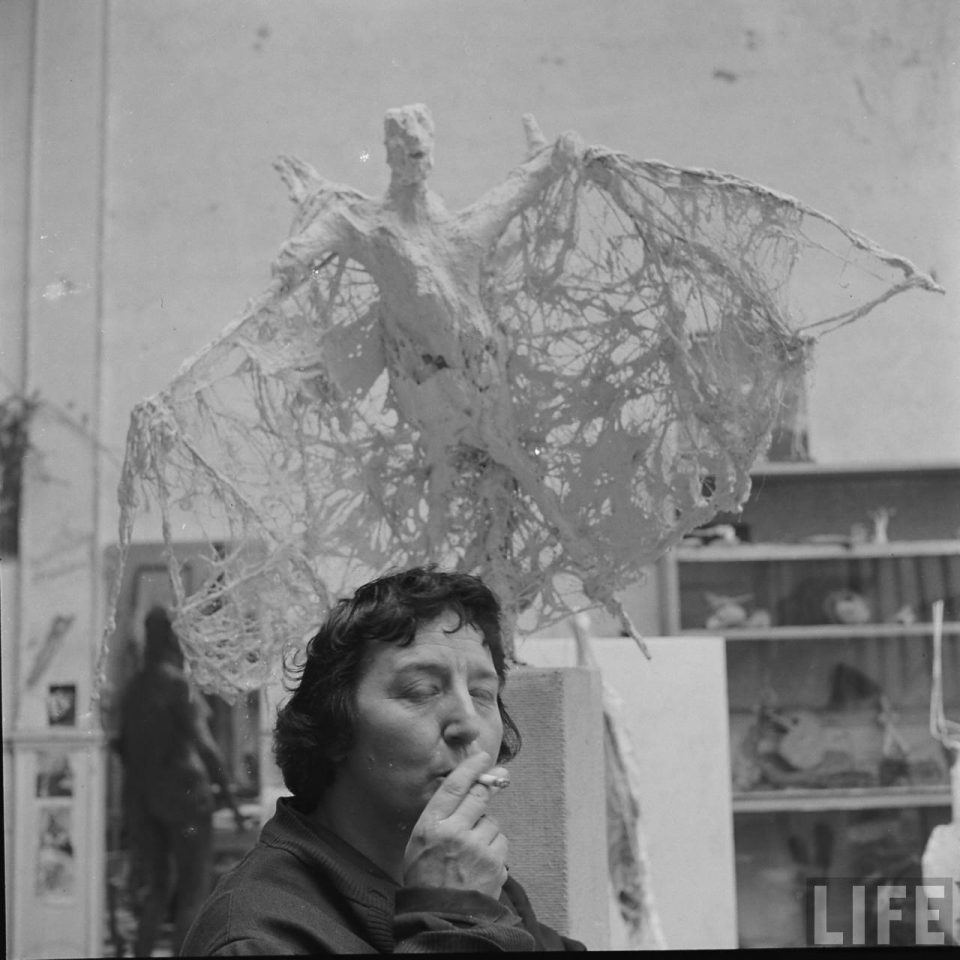

Germaine Richier (1902-1959) was a woman sculptor born in southern France in 1902. She attended the school of fine arts in Montpellier, and thanks to her talent, she was assigned to the sculptor Emile-Antoine Bourdelle (1861-1929), who became her mentor. He had studied with Auguste Rodin, but drastically changed style as opposed to his master. He aimed at representing pain with torn bodies in his sculptures, and this approach was much of an influence on Germaine’s style, as described as “the iconography of despair “ by Herbert Read – English art historian that argued for the philosophy of Existentialism adopted by Abstract Expressionists (see the first post “On Clyfford Still”).

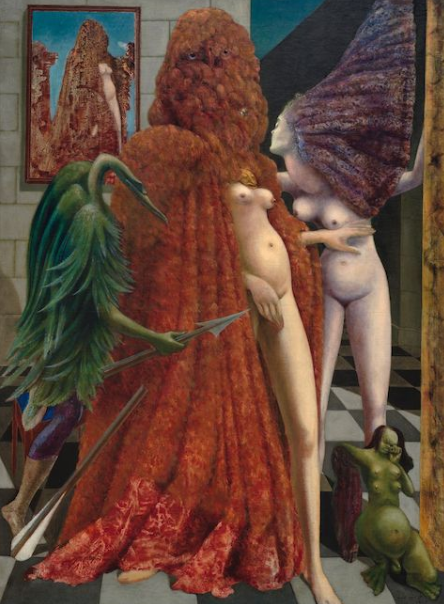

She had various sources of inspiration that influenced her way of modeling materials. She was involved in the Surrealist movement, and it can be read in Tauromachie which illustrates a scene of a matador who has just killed a bull. The title refers to “taureau”, which means “bull” in French, and this figure has been used extensively on a symbolic level by many Surrealist artists, such as Picasso in Guernica (1937). Indeed, Richier had hung a print of the iconic painting next to her bathroom mirror, and later said that Guernica was a central inspiration for her following artworks. Furthermore, the trident representing here the head of the matador is a direct reference to Max Ernst’s trident in Attirement of the Bride (1940), also present in the Guggenheim Collection in Venice.

However, Richier was mainly inspired by nature. she understood nature in all shapes and forms, in the sense that she would select both the beautiful and the ugly, both the apex and the decline of human nature. Her research on nature extended to the most microscopic details: she did not hesitate to collect natural elements such as leaves, insects and animal bones in her studio, to study and convey them accordingly through her sculptures. She had probably analyzed the skull of an animal to make the bull’s head in Tauromachie. In the 1950s many artists analyzed elements of nature as the first step in their artistic creation process and this approach was called biomorphism.

In fact, Richier’s approach results with hybrid creatures. “Hybrid” was a term introduced by the art historian René de Solier (1914-74) so to define Richier’s statues that layed in between human and animal renderings. It is through this approach that Richier managed to question what would make a human distinguishable from an animal. In Tauromachie, the bull’s head is dragged behind the matador, as a trophy. This is not a heroic scene, rather a cruel representation. Nothing prevents the matador from stopping him: his foot advances and even leaves the base of the sculpture in a convinced manner. We must question ourselves who is the beast in the end, the real animal or the matador? Who is more human? Here Richier greatly grasped the moral spirit of the postwar period. This is further stressed in the matador figure the knife is an extension of his hand, as humans are able to transform into beasts.

Richier had a peculiar technique that broke away from the traditional sculptural process. She would hardly make sketches as an initial study, and she admitted “the sketch is already complete, thus the artwork would only be a repetition of it”. She deliberately omitted this step and directly created statues marked by cracks and perforations as for her, a sculpture could not exist without the absence of feelings such as sorrow and anger.

Richier was considered as the greatest innovator of French sculptures in the fifties, and was even more recognized than the swiss sculptor Giacometti at the time. She went over London many times to exhibit art in times whem the Anglo-French political ties were strong and crucial. She held a solo exhibition at the Anglo-French art centre in London in 1947, and despite its closure in 1951, Richier’s influence was omnipresent in the English capital. . In 1952, the “London-Paris” exhibition organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art featured Richier along with other avant-garde figures including Francis Bacon, and in the same year the Franco-British sculptures were warmly received at the Venice Biennale. In 1955, her first Tauromachie was exhibited at Hanover gallery, in London.

It is probably between Richier’s active participation in London galleries and her arrival at the Venice Biennale that Peggy Guggenheim (1898-1979) met her and bought a version of Tauromachie. Since its first day in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Tauromachie has been put outside in the garden, next to a statue of Max Ernst. Interestingly, the art critic Pierre Restany (1930-2003) said the combination was glaring: Ernst’s piece was pure intellectual arrangement, whereas Richier was physically dynamic. By displaying Tauromachie in the garden, Peggy respected a wish of Richier: for the contemporary public to understand the role of sculpture today, it is necessary to place sculptures in places where their presence has been denied, such as public spaces and gardens.

This artwork can be seen at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, currently running the crowdfunding campaign “Together for the PGC” so to keep its collection and didactic activities open despite the COVID-19 crisis: https://www.guggenheim-venice.it/en/support-us/donate/